DIAMOND FACTS

Addressing Myths & Misconceptions About the Diamond Industry

Foreword

Natural Diamonds Have An

Extraordinary Story to Tell.

Natural diamonds are the Earth’s real treasures, exceptionally rare, and are mined today in a responsible way that supports livelihoods and contributes to conservation efforts around the world.

This new edition of Diamond Facts sets out to address the most common myths about the diamond industry, from those produced synthetically to natural stones unearthed from deep underground.

The first issue of Diamond Facts was well received by journalists, retailers, consumers and business leaders in our industry. As a single point of reference for data, it gave the natural diamond industry an accurate and consistent voice for the first time. This unified voice has had a positive impact on press stories and other influential conversations around the world. Narratives are more factual and balanced than those seen in previous years.

Natural diamonds are part of a dynamic industry, and the market is always subject to change. The information we share must reflect these changes too. This new edition of Diamond Facts, part of our Diamond Reports series, contains updated data on myths included in the first edition and new myths addressed with previously unreported data. We hope that you find this update helpful, and we welcome feedback on other topics and data points that would be of benefit in future versions of Diamond Facts.

We also encourage you to explore our other reports in this series, including Diamonds of Canada.

We will regularly be issuing reports in partnership with leading experts, data organisations and diamond industry representatives*.

DAVID KELLIE – CEO, NATURAL DIAMOND COUNCIL

Introduction

In this updated analysis we continue to address misinformation about both natural diamonds and laboratory-grown diamonds.

Our focus is on providing clear, accurate and reliable information so consumers can make informed choices. As detailed in the research, the reader can use existing information to formulate their own opinions.

Misinformation is harmful for all stakeholders in the diamond value chain, whether that is the consumer, mining companies, investors or local communities involved in regions that rely on the production of diamonds for economic stability.

We are dedicated to creating a positive legacy for all these stakeholders through openness and unbiased research.

Our work details an investigation into questions often posed relating to environmental and social standards, alongside general misconceptions about the market, such as quantity of diamonds recovered.

We redress the claims that it is impossible to distinguish between a laboratory-grown diamond and a natural diamond, explore how consumers can navigate this when buying diamonds and detail the global regulations in place to protect purchasing decisions along the supply chain.

On the environment, we delve into the nuances of sustainability claims made by the laboratory-grown diamond industry. Alongside reviewing impacts on water, waste and chemicals, we also look at the emissions footprint of both natural and synthetic diamonds, and the process of responsible opening and closure of mines. We also include further examples on the impact of the natural diamond industry from manufacturers’ perspective.

Outdated and misleading narratives about social conditions in the natural diamond industry are also evaluated. We explore the ethical sourcing of natural diamonds, the heightened focus on transparency, and the adoption of technology to enhance traceability. The robust set of measures in place to enshrine the rights of the employees of Natural Diamond Council (NDC) members is included. Through spotlighting initiatives and social programs, we seek to communicate the positive impact the natural diamond industry has on the livelihoods of 10 million people, especially from diamond-producing countries.

By tackling outdated and factually incorrect narratives, we are able to collaborate with all stakeholders to better communicate the inherent value and benefit of natural diamonds, as well as ensure clear and accurate information is shared about the industry in order to build trust and cultivate transparency. This is married to our mission at the Natural Diamond Council.

A NOTE ON RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The findings of this analysis have been derived from a thorough review of a wide range of secondary research sources and the evaluation of internal research conducted on behalf of the Natural Diamond Council by globally respected third-party organizations.

Industry experts and independent sustainability advisors were consulted on the topics included in the work to inform the findings. Research was conducted at the beginning of 2023 and the data and results have been updated in 2024. Methodologies for calculations pertaining to environmental footprints have been detailed in the footnotes and where industry data gaps or inconsistencies exist, a range has been used to provide balance. We welcome increased levels of disclosure across the industry for both natural and synthetic diamonds to enrich and inform future research.

Key Findings

Is it possible to tell a laboratory-grown

diamond from a natural diamond?

FACTCHECK:

All laboratory-grown diamonds can be detected using professional verification instruments. These tools use a variety of technologies to detect the differences between natural diamonds that are formed over billions of years in the Earth, and synthetic diamonds that are produced over a number of weeks in a manufacturing environment.

Claims that it is impossible to distinguish between a synthetic, laboratory-grown diamond and a natural diamond are false. Since diamond crystals grow differently in nature from in a laboratory, their grain patterns, like those in wood, are different1.

Consumers want to be sure about what they are buying, and there are many instruments available to distinguish between natural and synthetic diamonds. There are also legal definitions, advertising guidelines and certifications to ensure that consumers are correctly informed. These are explored in the following chapter.

Industry professionals have, for many years, used specialist laboratory equipment to examine growth patterns, composition, nitrogen content, fluorescence and spectral signature to identify whether a diamond grew in the Earth’s mantle or if it was manufactured in a factory.

For example, production of colorless laboratory- grown diamonds requires almost the complete removal of nitrogen, a constituent of around 99% of natural diamonds2. The changes to impurities in natural diamonds produced by extended time under the Earth’s crust can lead to very different responses to ultraviolet light.

These studies have been applied to the development of screening and detection instruments that can be used to reliably detect all laboratory-grown diamonds3.

With the increased quantity of laboratory-grown diamonds on the market, it has become increasingly important to address the misconception that natural and laboratory-grown diamonds are indistinguishable. Doing so can help protect consumers, and ensure they understand the product they are buying, that is accompanied by the correct claims about its origin.

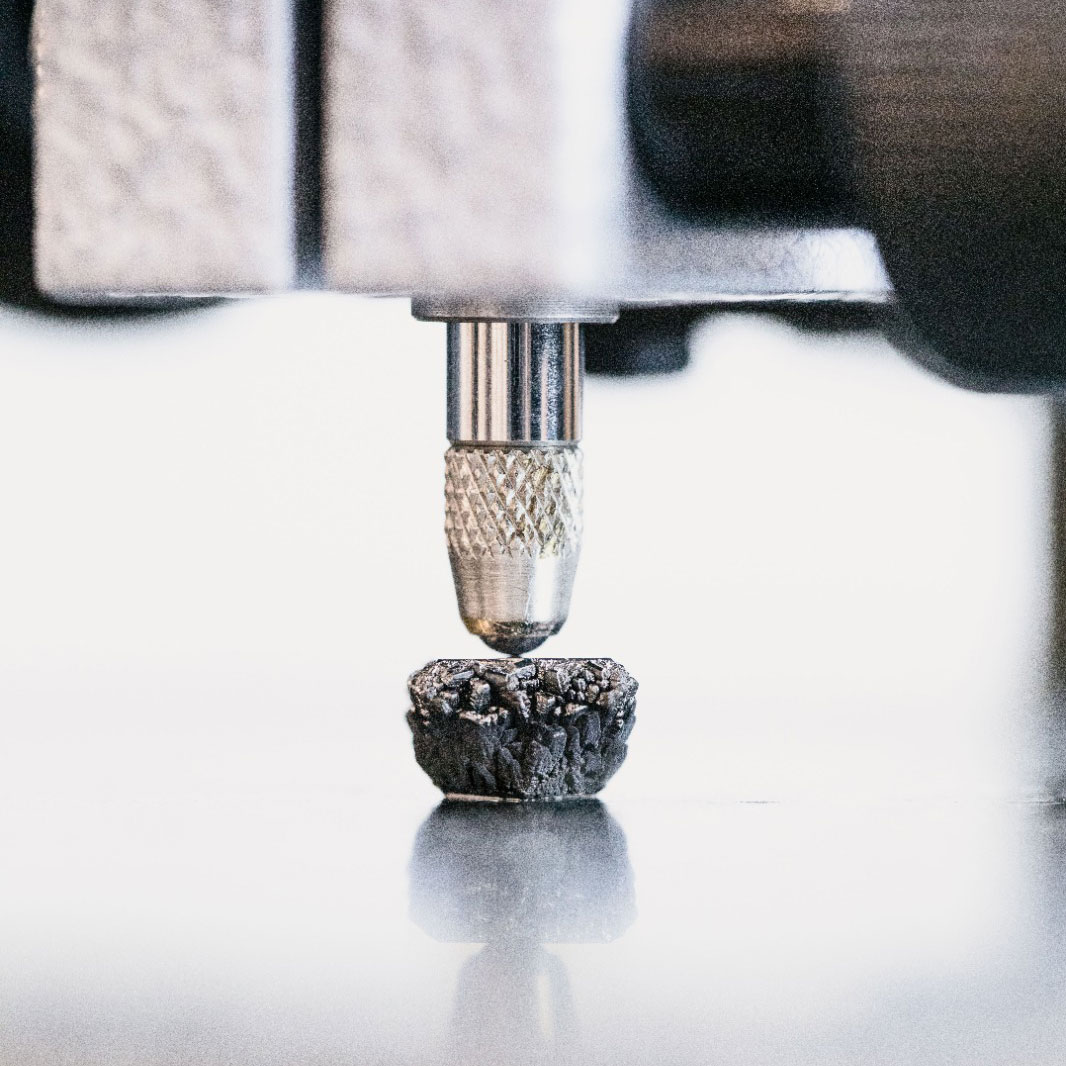

CVD LABORATORY-GROWN DIAMONDS

Differences which exist between natural and laboratory-grown diamonds are due to their differing creation processes. Natural diamonds were formed between 90 million and 3 billion years ago4 through the effect of high pressures and temperatures on carbon found approximately 100 miles below the Earth’s surface. They were subsequently brought to the surface by dramatic volcanic eruptions. Laboratory-grown diamonds are mostly produced in a number of weeks using one of two technologies.

The High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) method emulates the Earth’s method of diamond creation by using very high temperatures (1,300- 1,600°C) and high pressures. Alternatively, the Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) method produces a diamond crystal from a seed diamond plate by placing it in a hot gas chamber (900-1,200°C) with methane and hydrogen. The table below provides more detail about the differences in the creation processes and resultant rough and raw

diamond shapes.

What tools are used to detect synthetic and natural diamonds?

The structural differences between laboratory-grown and natural diamonds may not always be visible to the naked eye. However, there are more than 20 instruments available on the market which can help those involved in the diamond supply chain – like retailers, designers, and manufacturers – detect the difference.

According to the GIA, the instruments help professionals read a diamond’s spectral signature to determine its composition and identify whether it originated in nature or from a laboratory. Researchers are trained to check for graining patterns and ultraviolet fluorescence reactions, specific to laboratory-grown diamonds. But in recent years, changes in the quality and growth of CVD synthetic diamonds has led to greater dependence on spectroscopic identification techniques alongside the more traditional approaches16.

Further industry assurance

Diamond Verification Instruments are an integral part of the procedures that ensure pipeline integrity, preventing the mixing of synthetic diamonds and natural diamonds.

The NDC established the ASSURE program in 2019. It assesses the relative performance of Diamond Verification Instruments available on the market. Industry professionals can use the directory to guide them in choosing the instrument that will best serve their needs17.

Certification and legal guidelines on diamond definitions also help guide customers and stakeholders across the supply chain on whether they are buying laboratory-grown or natural diamonds. Read on to find out more.

How do I know whether I’m purchasing a

natural or a laboratory-grown diamond?

FACTCHECK:

Legal definitions and advertising guidelines exist to protect consumers and ensure they understand whether they are purchasing a natural or laboratory-grown diamond. Retailers obtain specific grading reports or certifications from independent organizations that can verify the origins and quality of natural and synthetic diamonds.

Legal Definitions and Advertising Guidelines

Clear diamond terminology exists to guide audiences on what can and cannot be classified as a diamond, as well as how to refer to laboratory- grown diamonds18.

Across the world, there are now global standards and national legislative requirements which must be followed by anyone selling these stones.

Key points from the standards are:

- The word ‘diamond’ used on its own always implies a natural diamond.

- Just three terms can be used to describe synthetic diamonds: ‘synthetic diamonds’, ‘laboratory-grown diamonds’ and ‘laboratory-created diamonds’. Terms that include the manufacturer’s name, followed by the word ‘created’ are also permitted in the United States of America.

Table 2 – Summary of Definitions and Guidelines

Understanding grading reports and certifications

Consumers can also be assured about the identity of their diamond by asking for grading reports or certifications23 (depending on the grading laboratory).

Laboratory-grown diamonds reports must always disclose in a clear way that they are laboratory- grown. For example, the GIA laboratory-grown diamond report24 provides information as to whether a diamond was made via CVD or HPHT.

Figure 1 – Sample of GIA Natural Diamond report25

Figure 2 – Sample of a GIA laboratory-grown diamond report26

Understanding environmental terms

Before diving into the questions about sustainability and environmental impact, take a look at these concepts.

CARBON FOOTPRINT: EXPLAINED

The quantity of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) expressed in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), emitted into the atmosphere by an individual, organization, process, product or event from within a specified boundary. The word ‘equivalent’ is used in the metric because other GHGs besides carbon dioxide, such as methane, are also released into the atmosphere. These are included in the measurement to create one standard figure for comparison and tracking over time.

CARBON INTENSITY: EXPLAINED

A measure of the carbon footprint (in terms of carbon dioxide and other GHG emissions) per unit of activity. For diamonds, carbon intensity is typically calculated by totaling the GHG emissions over a period from a laboratory or mine and dividing this by a measure of production in that period. This is usually either rough or polished carats.

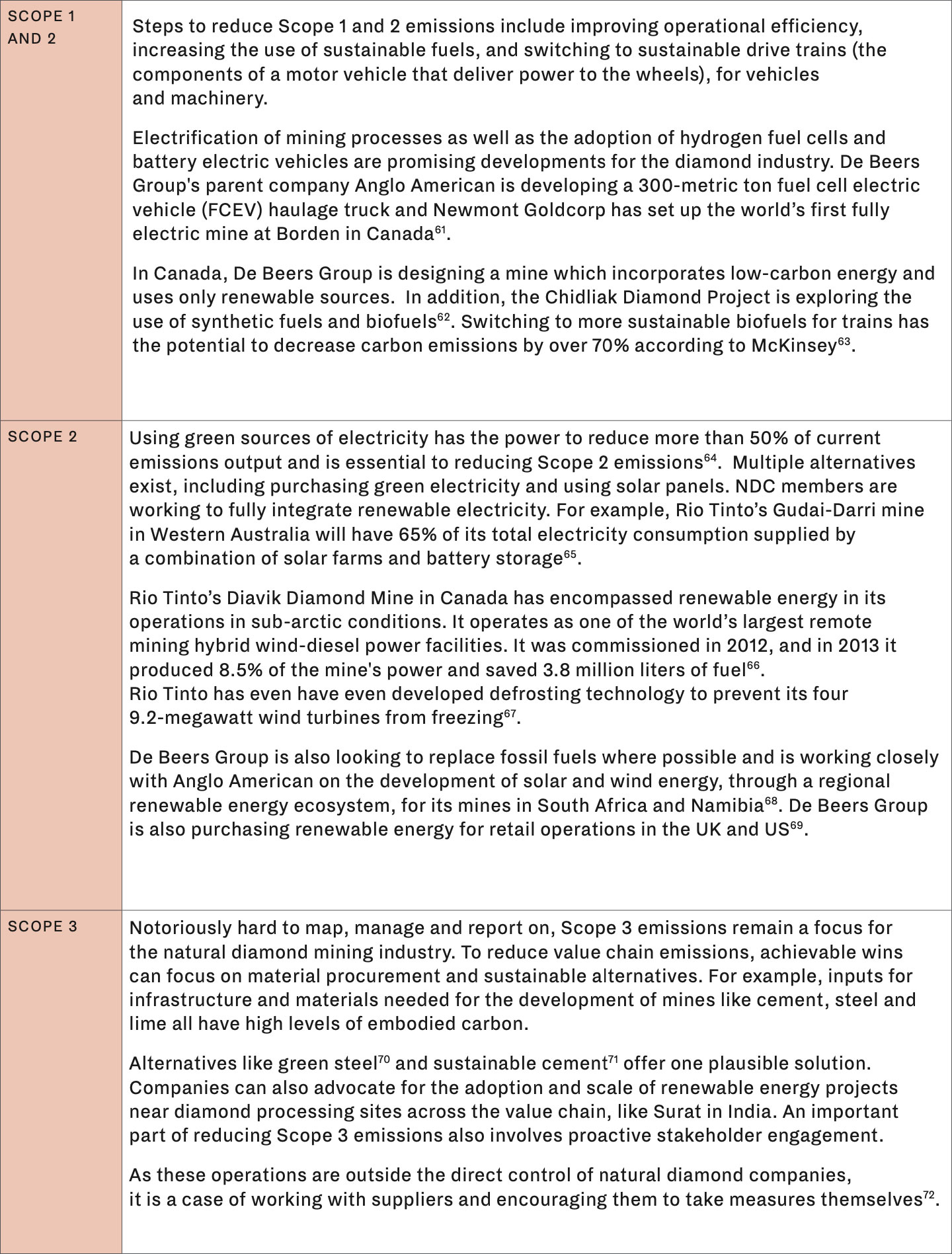

OVERVIEW OF SCOPES AND EMISSIONS ACROSS THE VALUE CHAIN

The emissions accrued can be separated into three overarching types; Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions27 28.

Figure 3 – Overview of scopes and emissions across the value chain

Scope 1

Scope 1 covers direct emissions that occur from sources that are controlled or owned by an organization (e.g., emissions associated with vehicles)

Scope 2

Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from the purchase and use of electricity, heating, cooling and steam. In using these sources the organization is indirectly responsible for these emissions.

Scope 3

Scope 3 covers all other indirect emissions that are not produced by the company itself but are a result of activities of various stakeholders up and downstream of the organization.

Are all laboratory-grown

diamonds sustainable?

FACTCHECK:

Laboratory-grown diamonds may not always be as sustainable as some claim. The manufacturing process, which lasts a few weeks, is energy- intensive, requiring temperatures similar to 20% of that of the Sun’s surface29. Over 70% of laboratory- grown diamonds are mass-produced in China and India where 62% and 74% of grid electricity is generated from coal30.

Publicly available research reveals that the claim that laboratory-grown diamonds always have a low, neutral or even negative carbon footprint is not true. The environmental sustainability of laboratory-grown diamonds depends on the energy, chemical, material, water, and waste management of the factory in which they are produced. It is also not possible to make a simplistic general comparison between natural diamonds and laboratory-grown diamonds. Each category has a range of production processes, geographical locations, power sources, productivity capabilities, and sustainability practices.

It is also a misconception that laboratory-grown diamonds are mining-free, as stated in some marketing campaigns. Synthetic diamond processes can require graphite and metals, and the reactors in which laboratory-grown diamonds are created are built with metals that all originate from mining.

Sustainability claims about laboratory-grown diamonds should be supported by evidence on their social footprint too, especially in areas relating to tax payments, employment and human rights, as well as the support provided for local communities in laboratory-grown diamond regions.

This chapter focuses largely on environmental sustainability and seeks to address these misconceptions with publicly available data.

Background on scale and emissions footprint

of laboratory-grown diamonds

The energy required to grow laboratory-grown diamonds depends on many factors including the size of the diamond and the type and age of the machinery used. For example, large stones require more energy to be manufactured. The most significant factor that impacts energy usage is the method used (HPHT or CVD) in their manufacturing. The emissions generated by laboratory-grown diamond manufactures depend on the amount of energy required and the energy source used. If electricity is sourced from the national grid, it will depend on the geographical location too and the extent to which the grid has been decarbonized with the use of renewable energy. Verified renewable energy certificates or similar (RECs) for the allocated usage is one way to confirm the energy is green and traceable/ independently verified.

Analyst Paul Zimnisky estimates that in 2024, approximately the majority of laboratory-grown diamonds were produced in China (46%) and India (26%)29, both of which have a heavy dependence on coal for electricity production. The $22 billion global laboratory-grown diamond industry is growing quickly30. Currently, according to Edahn Golan Diamond Research & Data, the market reached 15-20 million carats, whilst the industry’s capacity stood at around 6-7 million carats in 202031, indicating that production capacity is increasing.

The energy consumption of laboratory-grown diamonds

The energy mix where laboratory-grown diamonds are produced is important when considering how sustainable they are because the production of laboratory-grown diamonds is highly energy-intensive. As previously stated, there are two main methods of producing laboratory-grown diamonds: High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) and Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). The latter is significantly more energy intensive, mainly due to the use of high energy microwaves to produce the growth plasma.

In these processes, energy is required for extreme heating, up to around 1,500 degrees°C39 and for HPHT, pressure generation. A considerable amount of water is also required in some factories for cooling systems for reactors. Energy is also needed to stabilize the environment within the factory to ensure external conditions do not impact the growth of the synthetic diamond.

If electricity used in the production phases of laboratory-grown diamonds originates from non-renewable sources, this can contribute to laboratory-grown diamonds’ GHG emissions.

So, what is the exact carbon footprint of a laboratory-grown diamond? Few laboratory-grown diamond companies transparently disclose or verify such data and the truth is, there is no single agreed-upon figure. It is dependent on multiple factors including the method of production, the region and the methodology used to calculate the footprint. Sphera have estimated that the average emissions per polished carat produced by the CVD process can vary from 260kg C02e to 612kg CO2e in India40. In the instance that 100% renewable energy is used, then their research estimates this figure can be as low as 17kg CO2eq per polished carat of laboratory-grown diamond41.

CHEMICAL VAPOR DEPOSITION: EXPLAINED

The CVD diamond growth process involves placing seed crystals in a chamber that is filled with gas and heated to temperatures of 900- 1,200°C. Microwaves heat the gas into a plasma from which carbon atoms are deposited onto a seed crystal to form a diamond. The entire process usually takes three weeks to a month before the diamonds are ready to be cut and polished36.

CARBON INTENSITY: EXPLAINED

HPHT involves placing a diamond seed into a capsule which is placed into a press. The capsule is heated to temperatures of 1,300- 1,500 °C with pressures above 870,000 pounds per square inch. According to the GIA, this pressure is roughly equivalent to the pressure exerted by a commercial jet airplane if balanced on the tip of a person’s finger37. Metal in the growth capsule melts and dissolves the high-purity carbon source and carbon atoms are then deposited on the seed crystal to generate diamond growth38. Following conversations with industry professionals, we learnt that each HPHT reactor can weigh around 50 tonnes.

The carbon footprint of a 1 carat cut and polished laboratory-grown diamond

Figure 3 – The carbon footprint of a one carat cut and polished laboratory-grown diamond. Source: Sphera42

Within the laboratory-grown diamond market, different producers use different reactors in their production processes, which have varying energy efficiencies. This further impacts the accuracy of generalized figures that are often used. Just as some natural diamond companies use renewable energy, there are instances where laboratory-grown diamonds use renewable sources for their processes. Hydropower is a reliable renewable source and it can provide a constant source of high-intensity energy that is required for the growing process of a synthetic diamond. In these instances, it is fair to say that these laboratory-grown diamonds are more environmentally sustainable than orthodox mass-produced laboratory-grown diamonds where factories and machinery rely heavily on fossil fuels and non-renewable sources.

To navigate these complexities and if it is of interest, buyers should ask for carbon footprint data from the specific laboratory-grown diamond factory that produced their diamonds. There is limited data and transparency about carbon emissions from laboratory-grown diamonds.

Also, claims that laboratory-grown diamonds always have a lower carbon footprint and are therefore always more sustainable than natural diamonds are not true. The answer is dependent on numerous variables, especially in the natural diamond recovery process. These include geography, the mining process44 and the use of renewable energy.

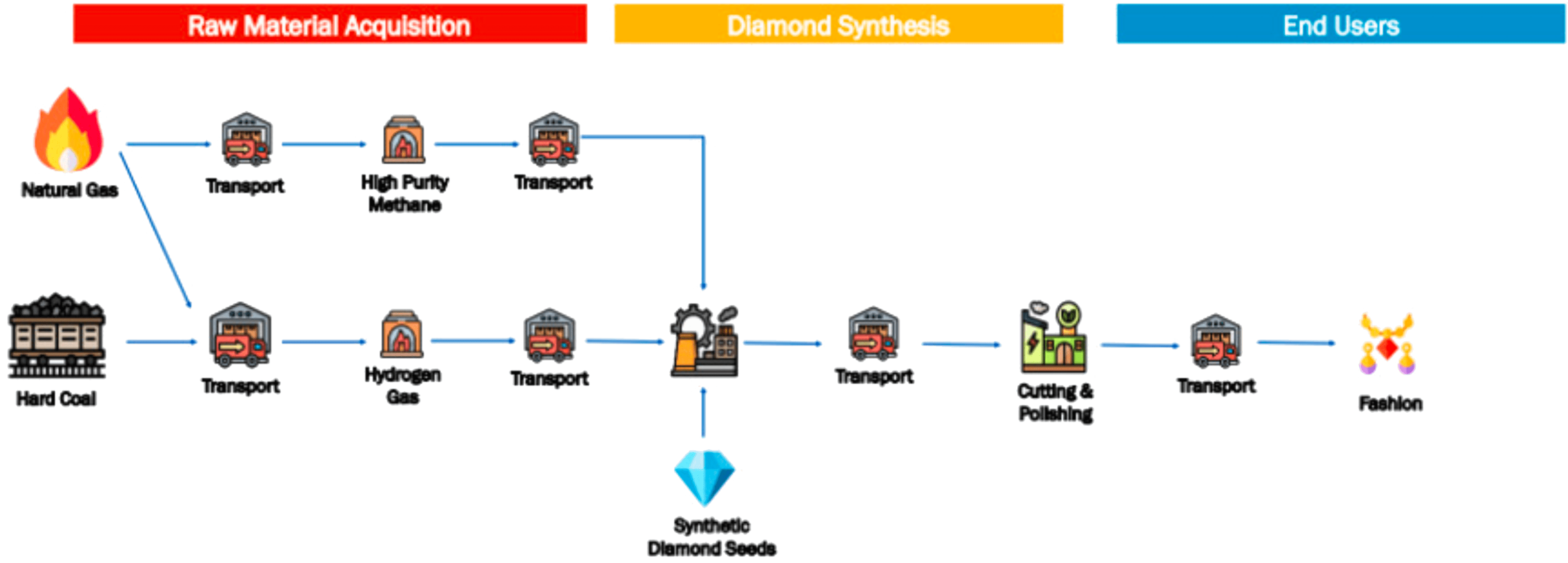

There is a common misconception that laboratory- grown diamonds are always mining-free. This is not entirely true. Laboratory-grown diamond synthesis requires the production of machines to carry out various processes. Machinery and machine processes involved at laboratory-grown diamond factories, like the presses, are made of high-grade steel, a material that has a high level of embodied carbon45. Additionally, manufacturing HPHT synthetic diamonds requires graphite, metals like nickel, iron and cobalt and pyrophylite – albeit in small quantities46. Equally, synthetic diamonds produced via CVD require methane and hydrogen. Methane is generally sourced from the mining of fossil fuels like gas, oil and coal47.

While hydrogen may be an emission-free fuel at the point of use, the energy density and energy losses involved in making it can pose a challenge. Unless the hydrogen is certified as green, it will not be emissions-free. Hydrogen has a lower energy density by volume compared to conventional fuels, requiring compression or liquefaction for storage and transport, both of which are energy-intensive processes that can reduce the overall efficiency of hydrogen as a fuel source, which could be as low as 25%43. The same principle applies to methane, unless the source is renewable feedstock

The detailed process of raw material extraction for laboratory-grown diamonds can be found in the Annex, at page 58.

On water usage, some HPHT factories require the use of large volumes of water to cool their equipment.

In China, where the majority of HPHT production takes place, factories use common water reservoirs to cool the HPHT presses and this reservoir water can be used multiple times. Research has found that in general, water consumption for the HPHT and CVD methods is materially insignificant, approximately 0 and 0.002 m3 per carat, respectively44. When it comes to exact figures on water recycling, there is little publicly available data on this to review.

A NOTE ON GREENWASHING

The global crackdown on greenwashing, specifically on misleading environmental claims, has affected the sustainability statements made by certain producers of laboratory-grown diamonds.

The Federal Trade Commission in the US sent warning letters to companies in 201945 regarding their diamond advertisement disclosures. It noted that any campaigns that claimed products were ‘eco-friendly’, ‘eco-conscious’, or ‘sustainable’ without specific evidence or data to back this up would be placed under review46.

It also started a public consultation process with the purpose to review its Green Guides. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published its Green Claims Code47 and France has brought in fines against companies found to be greenwashing48.

The European Union has also announced a set of new legislations aimed at tackling eco-claims. This underscores the importance of ensuring that any sustainability claims made by producers of laboratory-grown diamonds can be sustained and are underpinned by robust evidence.

What about laboratory-grown diamonds’ social sustainability performance?

Any broad claims that laboratory-grown diamonds are always a sustainable option must consider the social implications of the industry across the entire supply chain too.

Whilst this chapter has focused a lot on environmental sustainability, social conditions relating to employment and human rights, as well as the impact and mediation with local communities in laboratory-grown diamond regions, are fundamental to ensuring that when it comes to water usage, laboratory-grown diamonds can justify their ethical sourcing claims.

There is less access to published data and information about the social footprint of laboratory-grown diamond manufacturers and they are not held to account on reporting guidelines.

Additionally, as laboratory-grown diamond production has a business model that relies on technology-based manufacturing, the number of employees it must hire for direct production is significantly smaller than that of the natural diamond industry. There is also much less local procurement and incomparably less infrastructure and social investments made or partnerships developed with local communities.

This means that laboratory-grown diamonds do not have the same socio-economic benefits for communities or a positive social multiplier effect as natural diamonds have. The natural diamond industry operates largely in developing countries, so it contributes to the important economic development of producer countries.

Read more about this later on in our study.

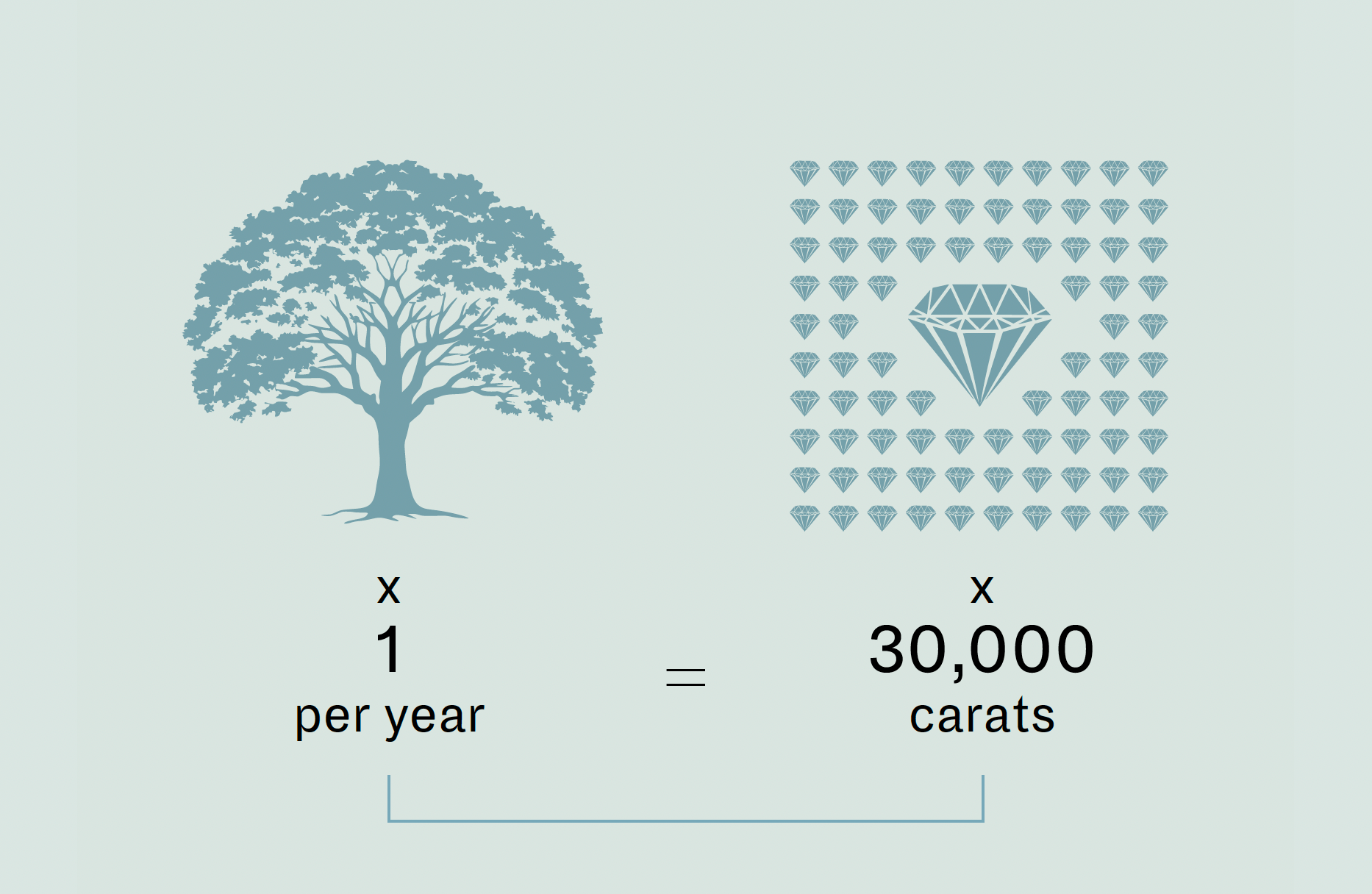

Accurate depiction of impact in carbon capture claims

A number of laboratory-grown diamond producers and retailers make certain sustainability claims such as offering carbon-negative products, as well as capturing carbon.

Although some of these organizations highlight their use of carbon capture technology as an important way to mitigate the environmental impacts of production, data shows that the actual volumes of CO2 contained in these diamonds is minuscule.

Carbon capture usually involves collecting CO2 from industries that emit high levels of greenhouse gases, like fossil fuel power generation, and injecting it deep into geological formations. An independent report by Prizma explains49 that carbon capture, storage and utilization facilities currently recover over 45 million metric tons of CO2 annually.

In comparison, the carbon locked in laboratory-grown diamonds is negligible and therefore the actual impact does not match their green claim. The amount of carbon locked in a carat of laboratory-grown diamond (0.2 grams of carbon) is the equivalent of the carbon emitted when sending and receiving one to two emails.

The report by Prizma also found that claims of CO2 capture or “carbon-negative” claims mainly refer to the actual creation of unpolished laboratory-grown diamonds, meaning when the seed crystal is placed into a kiln, high-pressure temperature apparatus, or vacuum chamber. Yet this one activity alone does not represent a laboratory-grown diamond’s true carbon footprint.

Laboratory-grown diamonds are refined in carbon-intensive industrial environments, with significant resources and capital required to meet production targets. Steps such as cutting and polishing, setting in precious metals, marketing, packaging, and distribution all generate CO2 and require significant water, computational power, and capital. Laboratory-grown diamonds will also move between facilities as they are being polished and displayed in jewellery, further increasing the carbon intensity.

Carbon Capture Claims

In one year, a mature tree will absorb on average more than 48 pounds of CO2 from the atmosphere (and release oxygen in exchange!). This is the equivalent of carbon locked in close to 30,000 carats of laboratory-grown diamonds.50

What is the natural diamond industry

doing to reduce its carbon footprint

and protect biodiversity?

FACTCHECK:

The natural diamond industry has set out on its journey to decarbonize in line with global climate targets. As part of their carbon reduction strategies, NDC members are developing renewable energy projects, often in developing countries where it is harder to source energy, as well as engaging in carbon offsetting projects and investing in programs to sequester carbon.

Companies like De Beers Group are committed to becoming carbon neutral by 203054 and Rio Tinto has set the goal of achieving net zero emissions by 205055.

The natural diamond world protects the biodiversity of an area that is considerably larger than the land they use. As much as 99% of the waste from diamond recovery is rock and 84% of the water used in diamond recovery is recycled53. The natural diamond industry abides by global environmental standards and stringent national laws

Before a single diamond is recovered, environmental permissions must be granted by governments with a legal obligation for ongoing monitoring, reporting, and closure plans.

The previous chapter sought to address misconceptions surrounding sustainability claims made about laboratory-grown diamonds. Now, we look to the natural diamond industry to explore how leading players are focusing on mapping and reducing their carbon footprint.

Factors that influence the difference in carbon emissions recorded by the industry

There are many contributing factors to the difference in carbon emissions recorded by the industry. These include mainly the availability of clean energy at mine locations, the production or yield capacity of a mine, and exactly which stages of mining are included in methodologies.

It is estimated that for a 1 carat polished natural diamond, the emissions are 106.9kg CO2e in 2019 (Scope 1 and 2)57. This equates to driving 265 miles in a medium-sized car that runs on gasoline and driving just less than the distance between Los Angeles and Las Vegas58.

How is the natural diamond industry working to decarbonize?

The natural diamond industry has set out on its journey to decarbonize in line with global climate targets. Leaders like De Beers Group have set the goal of becoming carbon neutral across their operations (Scope 1 and 2) by 2030 and are making progress, having achieved a 6% year-on-year reduction in energy intensity in 202359. Progress is tracked against a detailed pathway to carbon neutrality. Rio Tinto has the goal to reduce GHG emissions for Scope 1 and Scope 2 by 50% by 203057.

There are many opportunities for large-scale mining companies to reduce their Scope 1-3 emissions and NDC members are demonstrating progress. This section outlines how companies are working to decarbonize and where future efforts can be concentrated.

Reducing impact through carbon absorption, offsetting and conservation projects

Beyond emissions reduction strategies, NDC members are actively involved in offsetting projects and conservation efforts that help to remove carbon from the atmosphere and thus contribute to their climate goals.

For the emissions that cannot be mitigated or replaced with alternative energy sources, companies are engaging in offsetting projects like the Wonderbag initiative, which reinvests carbon offset financing back into communities and is verified by numerous carbon standards and protocols64.

A final example is CarbonVault, which is a research program supported by De Beers Group that is dedicated to exploring ways to lock away carbon in kimberlite65.

Petra Diamonds also joined the initiative looking at carbon sequestration through the mineralization of kimberlite tailings, in partnership with academic institutions. A publication resulting from the research states that weathering of coarsely processed kimberlitic material supports a diverse microbial community and produced secondary carbonate minerals. The occurrence of photosynthetic bacteria suggests these organisms may have served as a catalyst and a conduit for the transformation of atmospheric CO2 into (Ca, Mg) carbonates. The observation of these carbonates in historical kimberlite residue exemplifies the capacity for these anthropogenic deposits to sequester carbon, providing a novel carbon capture process for the diamond industry66.

SPOTLIGHT:

DE BEERS GROUP AND KELP BLUE

De Beers Group has launched a partnership for a pilot of its first nature-based climate solution. It has invested $2 million in Kelp Blue, a company that plants kelp forests across the world to improve the health of oceans, whilst also sequestering carbon emissions 67. Together, De Beers Group and Kelp Blue are working to plant a giant kelp forest off the coast of Namibia, helping support an ecosystem for 800 species 68.

IMAGE: DE BEERS / KELP BLUE

What is the natural diamond industry doing to protect biodiversity?

FACTCHECK:

Members of the NDC are always working, often in partnership with governments and local communities, to reduce the impact that natural diamond mining can have on the environment. As much as 99% of the waste from diamond recovery is rock and 84% of the water used in diamond recovery is recycled 69. The focus on stewardship of diamond mines by NDC members begins from the exploration phase through to the closure phase and is regulated by global environmental laws as well as national and industry regulations.

Every diamond mining operation has a different environmental impact, depending on the type of mining involved – whether it is alluvial, beach, marine or pipe mining. Equally, it is important to distinguish between artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) and modern large-scale diamond mining when discussing the environmental impact. ASM represents 10-15% of the natural diamond market70 and refers to mining by individuals, groups or cooperatives that often take place in the informal sector of the market71. There is often limited data available on the footprint of the ASM sector. These smaller organizations, even when publicly listed, may face fewer requirements for compliance with regulations and reporting standards. There are numerous operational measures being taken by the natural diamond industry to mitigate and reduce the impact on the environment. This includes conservation efforts and rewilding projects as well as waste and water management.

There are numerous operational measures being taken by the natural diamond industry to mitigate and reduce the impact on the environment. This includes conservation efforts and rewilding projects as well as waste and water management.

Information surrounding diamond recovery processes provided by NDC members details that no chemicals are used in the process, making it one of the cleanest forms of mining. There are changes to the landscape during the period of mining as it creates waste rock piles. However, these are reclaimed by the landscape as part of mine closure plans which are done under the strict supervision and approval of local communities and governments. Topography is not the same as damage. Land can be restored to land use acceptable to the local community.

In recent years, there has been an important focus on water reuse and recycling. During the diamond mining process, water reuse and recycling members consume water from a variety of sources including surface water, groundwater, and third-party supply72. As diamond recovery is reliant on a mechanical crushing process, water is more suitable for recycling and reuse73. Large-scale mining companies are working to reduce their dependencies, especially in water-scarce regions, by promoting the use of water recycling. For example, in 2022 Petra recorded that their water recycling initiatives had resulted in 80% of the water used being recycled on-site74.

What is the industry doing about the waste from mining?

Over 99% of waste produced by NDC members is rock, which is disposed of on-site and eventually reclaimed as part of the landscape during the mine closure and rehabilitation75. De Beers Group separates non-mineral waste at the source across a variety of materials ranging from metals, glass and plastic through to batteries76. De Beers Group majority shareholder Anglo American has also developed a Materials Stewardship strategy to encourage waste management focused on the principles of the circular economy77. Petra Diamonds recorded in 2022 that it had recycled 85% of waste from its local operations78.

Large-scale mining companies recognize the value of biodiversity and ecosystem services. They employ geologists, biologists and environmental experts to develop programs and ensure all operations are in compliance with environmental regulations and that the land is managed and protected correctly. Through policy and reporting standards, the companies are committed to regular monitoring and sharing information on energy usage, air quality, vegetation, and biodiversity impact.

Research conducted by environmental consultancy ERM details NDC members efforts to work towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 15 – Life on Land. NDC members’ protect close to four times the land they use for mining through biodiversity conservation and wildlife protection. At a significant 2,020 square km, the size of the land conserved for biodiversity is equivalent to the size of the total area of New York City and Los Angeles. It is also comparable to the size of four cities, New York City, Washington, Chicago and Las Vegas combined (1,912 square km) 79.

Here are some examples. De Beers operations are implementing measurable actions aimed at preventing biodiversity loss and restoring and protecting ecosystems at scale. To reach the Group goal of net-positive impact by 2030, each operation requires an active Biodiversity Management Programme. In 2023, all operations made significant progress on their biodiversity baseline assessments. This complex work has combined field data with remote and innovative technologies to provide a baseline condition of significant biodiversity within each operation’s area of impact. The company notes that several of their operations measure compliance against the Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) biodiversity protocol, an industry-led voluntary certification program developed by the Mining Association of Canada80.

As part of the focus of the De Beers Group on protecting the natural world, they protect land for dedicated conservation of flora and fauna in South Africa and Botswana.

These properties include the Venetia Limpopo Nature Reserve in South Africa and the Orapa Game Park in Botswana. As diamond mines and the surrounding areas are highly secure, these properties provide a safe haven and vital habitat for some of southern Africa’s most celebrated and threatened wildlife, including rhinos, elephants, giraffes, and zebras.

This rich diversity of species is thanks in large part to the dedicated conservation efforts of the on-site De Beers ecology teams that manage the reserves. In addition to providing protected habitat, the properties are also host to scientific research programmes as well as educational programmes with local schools and tourists to support local economic development.

Another case is the De Beers Group Moving Giants initiative, which has worked to safely translocate elephants with the Peace Parks Foundation.

Other examples include Petra Diamonds, who have funded a four-year BirdLife Africa Secretarybird project on an endangered bird species. This resulted in the publication of a scientific article on the feeding and breeding of the bird species.

Petra Diamonds has also started a bee pollinator conservation project where bees are removed from the mining site and placed in a safe environment, empowering community members to engage in beekeeping for economic gain. Operational sites have trained beekeepers to place bees in well-secured hives. One notable initiative involved the Cullinan Diamond Mine, which repurposed an old shipping container into a mobile beekeeping unit. Using refurbished building materials and furniture sourced from the mine, the container was equipped with all the necessary tools for honey extraction and bottling.

In FY2024, this beekeeping unit was donated to Bongi Bees, a training facility founded by Lulu Letlape. Bongi Bees focuses on empowering local women through sustainable beekeeping practices. The addition of the “honey factory” container significantly boosted Bongi Bees’ honey production, increasing from 20 kg per week to 80 kg.

Rio Tinto is managing Wildlife Monitoring Programs. Similarly, RZM Murowa have a strict relocation program of crocodiles and pythons with the support of the local Parks and Wildlife Authority.

Invertebrates constitute most of Earth’s species and are vital to global ecosystem functioning. They are considered in environmental impact assessments and monitoring programmes. Due to the hyper-diversity of invertebrates, the use of indicator groups is of great value in the rehabilitation progress assessment at mines.

An unusual new species of ant belonging to the genus Solenopsis (commonly known as ’fire ants‘ or ’thief ants‘) was discovered during an environmental impact assessment survey at Petra Diamonds’ Cullinan Diamond Mine in 2001. Subsequent surveys at this and other sites throughout South and Southern Africa have resulted in the discovery of several other new and potentially new species. A description of the first new species found at Cullinan Mine will be of great significance and will result in the re-definition of genus-level characters of Solenopsis worldwide. The proposed species name for the first new Solenopsis species discovered here is ’taemane’, North Sotho for ’diamond’, to commemorate the site where it was found.

Mine Closure: impact, regulations and planning

NDC members are focused on creating a sustainable legacy and going above and beyond regulatory and environmental compliance. All members have to comply with international and environmental legislation aligned with standards including ISO 14001, which provides a framework for effective environmental management systems. This runs alongside reporting requirements in line with the GRI Mining and Metals Sector Supplement and other corporate sustainability reporting guidelines and frameworks81.

The stewardship of mines throughout their life cycle underscores the strict rules that mining companies must follow, related to both post-mining land use and economic plans to support the socio-economic prosperity of communities. Permits are not provided without details of impact mitigation, a sophisticated closure plan and proof of financial resources to support a sustainable exit.

A mining closure plan involves how a site would be managed at the end of its productive life, the activities to achieve closure goals and how the land can be rehabilitated82.

In an interview, a representative from De Beers Group noted that “We need to be planning for closure right from the design of the mine.” 83, which is what the large-scale mining industry is doing.

The Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals & Sustainable Development outlines that closure plans should include stakeholder engagement, risk analysis, close monitoring and maintenance as well as financial assurance and many other areas84.

Varying geographies have a range of regulations pertaining to environmental mining regulations and closure plans. For example, in Canada there is the Canadian Environment Protection Act administered by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

According to Ryan Fequet, Executive Director for the Wek’èezhìi Land and Water Board, the Northwest Territories (NWT, Canada) have Land Claim Agreements and a unique, progressive and empowering piece of legislation called the Mackenzie Valley Resource Management Act. This ensures a transparent, holistic and integrated approach to renewable and non-renewable resource management. Regional Land and Water Boards of the Mackenzie Valley support licensing on everything from water use and wastewater management to land use. These licenses have strict reporting and monitoring requirements too85. Further expansion of their policies and guidelines can be found in the Annex.

In Canada, the Mining Association of Canada’s Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) standard supports mining companies as they manage key environmental and social risks. An independent board completes an environmental assessment and also uses tools like Socio-Economic Agreements, which sets out commitments and predictions made by a company regarding their impact. This is then monitored and published in a yearly report to the government of the Northwest Territories86.

In South Africa, mining regulations begin at the scoping phase all the way through to closure, with mining becoming a listed activity in 2010. The environmental provisions of the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) No. 107 of 1998 now apply to mine closure certification, resulting in mines having to comply with stipulations of this Act before qualifying for closure87. NEMA underlines that public consultation is essential at the early stages of projects.

In Australia, the Government of Western Australia Department of Mines and Petroleum (2017) Mining Rehabilitation Fund – Guidance and The Mining Rehabilitation Fund (MRF) Act of 2012 covers many important issues related to funding the closure and rehabilitation of abandoned mines. This goes against the narrative that mining companies simply enter a region and leave with no accountability88.

IN FOCUS: MINING REGULATIONS AND GUIDELINES

Whilst not exhaustive, the list below details initiatives, guidelines and frameworks that highlight the level of regulation on the opening and closure of mines:

- Australian Government (2016) Mine Closure – Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry: introduction to mine closure and current leading practices from an Australian perspective.

- ANZMEC (2000) Strategic Framework for Mine Closure

- ICMM (2008) Planning for Integrated Mine Closure – A Toolkit: provides a broadly conceived life cycle and risk-based approach to closure planning.

- Mining Association of Canada (2008) Towards Sustainable Mining – Mine Closure Framework: an industry-led initiative to articulate the commitment of member companies to promote responsible mine closure.

- NOAMI (2010) Policy Framework in Canada for mine closure and management of long- term liabilities

- World Bank Multistakeholder Initiative (2010) Towards Sustainable Decommissioning and Closure of Oil Fields and Mines: provides a policy-oriented series of toolkits related to closure for both oil fields and mines.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF) (2013) The IGF Mining Policy Framework: Mining and Sustainable Development: lays out a framework that provides a comprehensive model for policy that will allow mining to make its maximum contribution to the sustainable development of developing countries.

Responsible mine closure

With the closure of Argyle in Australia – one of the world’s most iconic natural diamond mines – responsible mine restoration has come into focus. It takes on average 10 years to open a mine. Having a closure plan is a prerequisite to opening a mine, in addition to social and environmental impact assessments which are audited, approved and monitored by governments and local community.

SPOTLIGHT: THE VICTOR MINE

Based in Ontario, Canada, the Victor Mine halted production in May 2019 and demolition of its operational facilities started in 2020. De Beers Group has worked to rehabilitate the mines’ waste rock repositories and separate recyclable and non-recyclable waste produced throughout the demolition.

It has planted over 150,000 spruce trees and rehabilitated approximately 328 hectares of the mine’s disturbed operational footprint, using commercial seed and seedlings propagated both onsite and offsite. The company is using field-based and remote- sensing programs to track progress101.

SPOTLIGHT: RIO TINTO – DIAVIK MINE

Set in the Northwest Territories of Canada, the Diavik mine, owned by Rio Tinto, is set to close in 2025, after opening in 2003. The company has designed the mine to minimize disturbance once it comes to the end of its life. Rio Tinto has used engineering technology and techniques that hold back the waters of the Lac de Gras to minimize disturbance to surrounding wildlife and communities. It has plans to build back the embankment to ensure lake water can flow back into the open pit102.

Further projects to support responsible mine restoration include Rio Tinto’s collaboration

with RESOLVE, a non-profit organization. They have worked together to launch Regeneration, which is a company that will use re-mining and processing of waste from legacy mine sites to support rehabilitation activities and restore natural environments. Rio Tinto has committed to initially invest $2 million into the company103.

Elsewhere, NDC members De Beers Group and Rio Tinto are working together on the Reimagining Closure project with the intention to identify opportunities for life after diamond mining in

the Slave Geological Province (SGP) in the NWT of Canada as mining activity winds down. This focuses on socio-economic planning and support whilst engaging with numerous stakeholders including indigenous governments, federal governments, mining companies, businesses, and communities as well as conservation bodies104.

The details of these efforts underline that the natural diamond industry is working to minimize the impact mines have on the environment through a focus on land restoration, as well as seeking positive post-mining opportunities via socio-economic rehabilitation for communities in surrounding regions.

Are natural diamonds rare?

FACTCHECK:

Natural diamonds are a finite resource. Global natural diamond recovery peaked in 2005, when rough diamond production was around 30% higher than in 2022105. The annual recovery of 1 carat diamonds is equivalent in volume to filling an exercise ball.

The process of natural diamond formation means that as an object, they are innately rare. Formation takes place across the span of millions, sometimes billions, of years and occurs in limited zones of the Earth’s mantle at extreme temperatures and pressures106

Natural diamonds are hard to find and have only been found in rock over the last 150 years. The first diamonds were found in caves in India nearly 4000 years ago and for a long time, this was the only known source. Over time, they have become prized for their perfect shape, hardness, rarity, fire resistance and intense light107.

These conditions contribute to their rarity, with the annual recovery of 5 carat diamonds and above would fit into a basketball108.

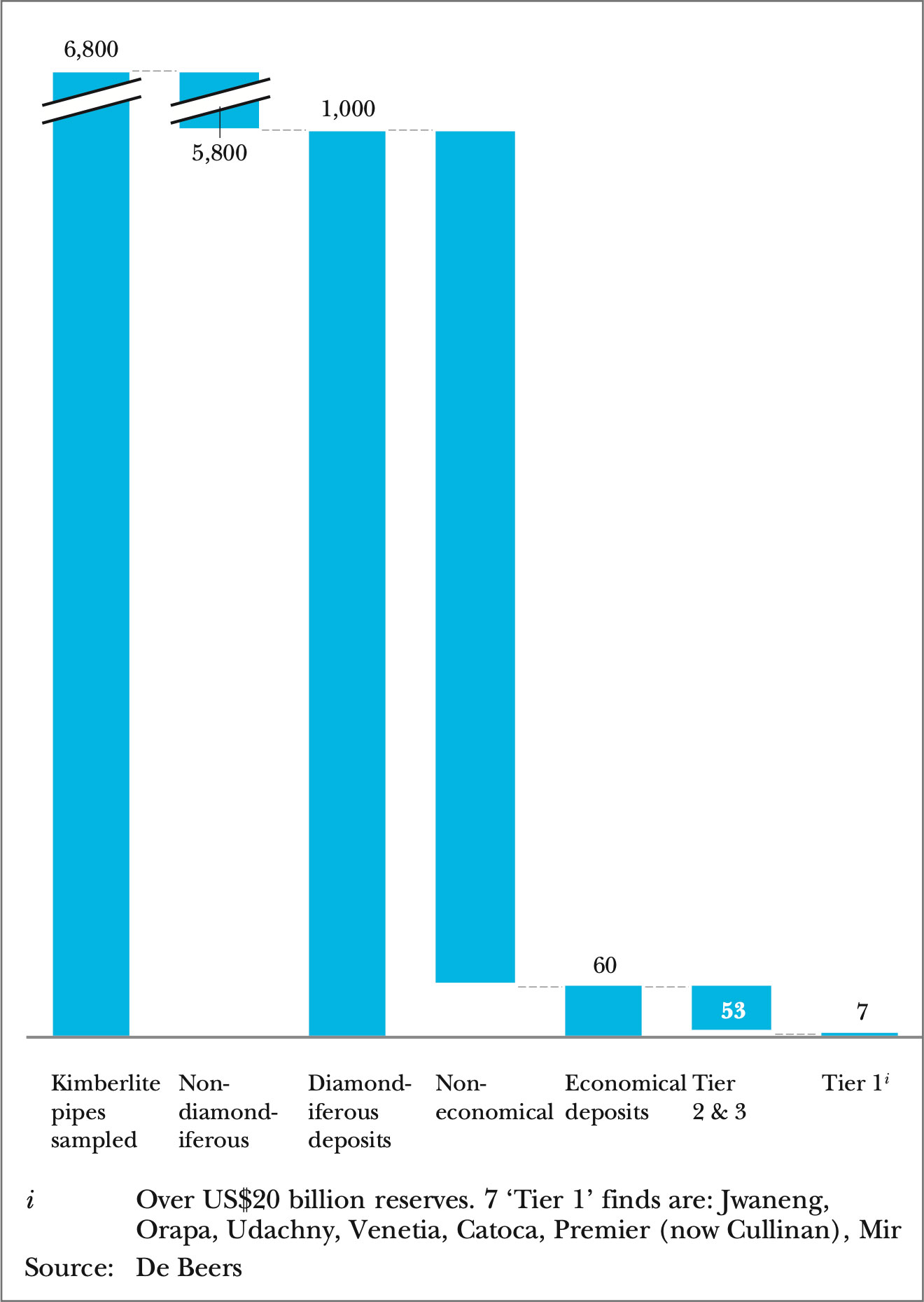

In fact, today there are only 30 significant natural diamond mines in production, with only 7 mines considered to be classified as Tier 1 deposits. Tier 1 deposits are those which have over US$20 billion in reserve109.

De Beers Group recorded that over the last 140 years, almost 7,000 kimberlite pipes have been sampled by geologists. Yet, approximately only 60 of these were deemed to be sufficiently rich in natural diamonds to be economically viable for large-scale diamond mining companies110.

Graph: Number of diamond deposits sufficiently rich to warrant development

Many industry experts and analysts believe that the annual recovery of natural diamonds peaked in 2005 at 177 million carats112. Though this recovery has fluctuated, leading analyst Paul Zimnisky notes depleting legacy mines and limited new supply sources, further punctuated by the Covid-19 pandemic, resulted in a significant production decline. Through his analysis, it is predicted that production is expected to remain within a range of 115-125 million carats annually, a much lower figure than 150 million carats recorded in 2017113.

A major contributing factor to this belief is the declining profile of existing mines and the small success rate of exploration. Petra Diamonds states that the success rate in diamond exploration is estimated at less than 1%114.

Data recorded via the Kimberley Process from 2014 – 2021 illustrates the gradual decline of rough diamonds recovered and traded under the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) over recent times.

Deep pockets and large financial investment are needed to explore new diamond mining opportunities.

Determining the economic viability of these projects also extends to different types of mining, including alluvial mining. Alluvial mining is a process where stones are found in riverbeds or shorelines after kimberlites have eroded over time. Approximately 10-15% of the world’s diamonds originate from alluvial mining, however, geologists have commented that often they cannot tell how many stones there are. This is a key piece of information in determining if reserves justify economic investment115.

The closure of mines which have reached the end of their economic lives include Argyle in Australia, owned by Rio Tinto which closed in November 2020, Victor Mine in Canada owned by De Beers Group which closed in 2019, Voorspoed in South Africa, owned by De Beers Group and Snap Lake, owned by De Beers Group in Canada116.

The termination of operations of mines like Argyle, which once produced up to 40 million carats a year is symbolic of the changing landscape of natural diamond mining117.

Further potential near-term closures include Diavik, Ekati, Nyurbinskaya and Almazy-Anabara which are expected to either reach economic depletion or conclude conventional mining by the end of this decade.

In fact, industry analyst Zimnisky notes that these mines currently account for a combined 17-20 million carats of annual production, representing approximately 15% of global supply118. This represents a significant supply change to the natural diamond industry. De Beers Group is also still exploring new opportunities and in 2022 signed Mineral Investment contracts with Angola to return to exploring the country for new sources119.

Is the industry stockpiling

diamonds to drive-up prices?

FACTCHECK:

Inventories of natural diamond producers fluctuate across periods of time, especially when they are broken down by size or quality of stones. This is because, unlike other industries, natural diamond producers cannot operate a just-in-time production model to match supply with demand. Inventories are also impacted by seasonal demand patterns and by external events such as the global coronavirus pandemic.

Comparisons of production and sales data for NDC member companies shows that over a business cycle, there is no evidence of deliberate stockpiling to systematically drive-up prices. This is because total production and total sales are in line with one another. Bain & Company compiled data from company reports and the Kimberley Certification process to estimate that upstream inventories (i.e. those at diamond mine sites and sorting offices) across the world fell by 40% in 2021, leaving them close to minimal ‘technical levels’120.

The factors impacting diamond inventories

There are multiple factors that cause diamond inventory levels to fluctuate over time.

Firstly, unlike other industries, there is a large variance in the size, color and quality profile of what diamonds are recovered each month. These characteristics are dependent on natural geological processes, rather than manufacturing decisions. It also takes several weeks and months for recovered diamonds to travel from mine to a point of sale.

This is because they must be sorted, typically into one of 15,000 categories of rough diamonds according to their size, shape and quality, before being sold or auctioned at sales that are typically held once a month121. Inventories therefore fluctuate particularly by type of stone.

Seasonal fluctuations in demand can also affect monthly diamond inventories. For example, consumer demand for jewelry is usually highest in the fourth quarter of the year, around seasonal holidays, which can impact the inventory upstream.

Additionally, external events like the global coronavirus pandemic in 2020 or the Financial Crisis of 2008 can cause a reduce in demand and therefore, impact inventories following such events when economies start to recover122.

Recent trends

So, what has happened to diamond producer inventories in recent times? As explored in the chapter on rarity, natural diamonds are a finite resource and their recovery peaked in 2005 following the closure of legacy mines and finding new deposits123. Production in 2021 was recorded to be 20% below the level of 2017124.

Supply depletion, alongside the strong market demand of 2021 as the world emerged from the pandemic has reduced the inventory of mining companies to low levels125.

Bain & Company compiled data from company reports and the Kimberley Certification process to estimate that upstream inventories (i.e. those at diamond mine sites and sorting offices) across the world fell by 40% in 2021, leaving them close to minimal ‘technical levels’ .

To review inventory trends, comparisons of published carat production and sales data over a business cycle can be assessed.

Whilst this does not provide a complete picture, when analyzed over a considerable time, it helps to demonstrate that total production and total sales are in line with one another and that therefore, there is no evidence of deliberate stockpiling to systematically drive-up prices.

According to Paul Zimnisky, upstream inventory levels remain at significantly low levels. Production data is available on companies’ websites126 and underlines how the industry is pursuing increased transparency when it comes to production and inventory management.

Through the UN and World Trade Organization mandated Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, explored in our chapter on ethical sourcing, international rough diamond trade is regulated and recorded. Data and statistics arising from the Kimberley Process indicate the levels of diamond recovery and paint a clear picture of the market’s production.

What have been the price trends for

laboratory-grown diamonds?

FACTCHECK:

Prices for laboratory-grown diamonds have fallen from 2016 to 2023. For example, in some cases the price of a 1.5 carat stone has fallen by over 74%. There is a widening price differential between laboratory-grown diamonds and natural diamonds. Whilst the price of natural diamonds has also fluctuated over the last 35 years, on average they have risen by 3% per annum.

How has the pricing of laboratory-grown diamonds changed over time?

Diamonds were first synthesized in a laboratory in the 1950s and the first synthetic gem-quality stones appeared on the market in the 1970s. In these early years, the stones were mostly small, and yellow or brown in color127 and production costs were high128.

Since the commercial development of CVD technology in the early 2000s, the production costs of laboratory-grown diamonds have fallen dramatically – in line with technological advances, economies of scale and competitive pressures as new producers have entered the market.

Additionally, machines that were previously used to make industrial diamonds have been repurposed for gems. Bain & Company estimated that in the 10 years from 2008 and 2018, the average production costs of a high-quality laboratory-grown 1 carat stone fell by 90%129. Retail prices of laboratory- grown diamonds have also declined, though to a smaller extent. When laboratory-grown diamonds began appearing in commercial quantities in the jewelry market around 8 years ago, prices were typically slightly cheaper than those of

natural diamonds.

However, as the laboratory-grown market has expanded, the relationship has diverged.

However, as the laboratory-grown market has expanded, the relationship has diverged.

For example, analyst Paul Zimnisky has noted that in 2016, a round, almost colorless, high quality, 1 carat synthetic stone cost around 10% less than a natural diamond. However by the close of 2022, the differential was as much as 80%, depending on the manufacturer. Zimnisky’s figures illustrate that a typical, generic, 1 carat laboratory-grown stone of this color and clarity was more than 70% cheaper than a natural diamond at the end of 2022.

Sample prices of man-made relative to natural over 7 years

Source: Paul Zimnisky (2023) State of the diamond market March 2023. Available here

How the prices of natural diamonds and laboratory-grown diamonds have changed from 2016 – 2023

Prices for laboratory-grown diamonds have fallen from 2016 to 2023, in some cases, for example for the price of a 1.5 carat stone, by over 74%. For example, according to Zimnisky’s “State of the diamond market” March 2023 report, in 2016, a 1.5 carat natural diamond would have cost $12,125, while a 1.5 carat synthetic would have cost $10,600 – amounting to a difference

of $1,525. However, early 2023, the retail price of a 1.5 carat natural diamond had increased to $13,625, whilst its laboratory-grown counterpart would have decreased in price to stand at $2,445 – representing a substantially larger difference of $11,180. Research conducted by The Gem Academy illuminates the difference132. By analyzing 2021 price data for natural diamonds and laboratory-grown diamonds available from two online retailers, they recorded that the cost of a 1 carat natural diamond was $7,355, whilst a 1 carat laboratory-grown diamond cost $2,110, representing a price difference of -71%. Across diamonds ranging from 0.5-3 carat weight, the research stated there was an average price difference of -66% across all sizes133.

The current pricing of natural diamonds

Natural diamond prices reflect their rarity and limited supply. Bain & Company conducted a historical analysis looking at data between 1970 and 2019, in which they noted that polished prices of natural diamonds had risen over the last 35 years by an average of 3% per annum134. Post- pandemic, Bain & Company noted that in 2021, rough natural diamond prices grew by 21% and that prices increased by 9% year on year for polished diamonds. Whilst this is below their historic maximums, it illustrated that both rough and polished prices were returning to pre-pandemic levels135. Zimnisky has tracked prices of rough diamonds since 2007. Based on an initial index value set at 100 on 31 December 2007, his rough price index stood at 183.4 at the end of March 2023, implying an average annual growth trend of 4% per annum136.

The differences in pricing structures between laboratory-grown diamonds and natural diamonds

In addition to the diverging price trends over time, these is also a difference in the pricing structures of laboratory-grown diamonds and natural diamonds. The supply, size and the available quality mix available of natural diamonds depends completely on geology, and as noted in previous chapters, large stones are very rare. The prices of different types of natural diamonds have therefore always reflected this rarity. For example, this means that a 2 carat stone costs significantly more than double the price of a 1 carat stone. As a laboratory-grown diamond is not dependent on geology, the main constraint is the production capacity of each company. A larger synthetic stone requires more energy and takes longer to produce than a smaller one, but the relationship is broadly linear – the production costs for a 2 carat stone are twice that of a 1 carat stone. Whilst prices of natural and laboratory- grown diamonds have diverged, the differences have not been uniform across all sizes and qualities. They have tended to be highest for larger stones. For example, Zimnisky’s data indicates that between the end of 2020 and the end of 2022, prices of 1 carat synthetic stones fell by 24% while prices of 3 carat stones fell by 45%.

Economic policies and geopolitical factors influence the price differential between natural

and laboratory-grown diamonds. The OECD has recorded that many countries are in a highly competitive race to attract diamond trading, with nations offering tax exemptions or special economic zones for activities like cutting and polishing137. To stimulate the production of laboratory-grown diamonds at a significant scale, India has implemented new policies to position itself as a competitive marketplace. For example, there has been a recent push by the Indian government to reduce import duties on diamond seeds, an essential component of lab grown diamonds, originating from China. In the latest 2023 Budget, the Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman abolished a 5% customs duty on imports of seeds used for the manufacturing of rough laboratory- grown diamonds138.

Do natural diamonds benefit the

countries where they come from?

FACTCHECK:

Members of the NDC are dedicated to reinvesting in and creating a positive multiplier effect across the communities they work with, in line with their commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals – especially on areas surrounding alleviating poverty, decent work, health and wellbeing, fair wages and reduced inequalities. Up to 80% of rough diamond value can remain within local communities in the form of local purchasing, employment benefits, social programs and investment in infrastructure as well as the taxes, royalties and dividends paid from the industry to respective governments139.

Perceptions about economic inequalities across the natural diamond supply chain are outdated and tainted by a history of power imbalances.

Today, this is no longer the case. The natural diamond industry has generated significant economic contributions to many developing nations that are diamond producing countries. This has created a positive multiplier effect for countries like Botswana and Namibia. The flourishing of these economies fights the paradox of the ‘resource curse’.

Enriching the lives of diamond mining communities

The natural diamond industry is often perceived as a mining industry that does not take care of the regions from which it extracts minerals and diamonds, and that operates only for the benefit of organizations in the West. Perceptions of legacy issues such as colonialism and corruption of large-scale diamond miners are often outdated. These companies are heavily regulated and are genuinely invested in the economic and social prosperity of the communities they have worked with for centuries.

The natural diamond industry supports the livelihoods of 10 million people across the world who are involved in the diamond supply chain140.

It is important to note that many mining companies are partially owned by local governments, which means they receive direct economic benefits and impact the strategic direction of the mining operations. This includes De Beers Group’s operations in Namibia and Botswana.

NDC member companies make a significant socio- economic contribution to the local communities and governments where they operate. This can be in the form of local employment and training, local sourcing of products and services as well as health and education programs and training for local suppliers and businesses, through investment in infrastructure. They aim to ensure that local communities share in the success of the mine whilst it is in operation and also prepare for their future after mine closure.

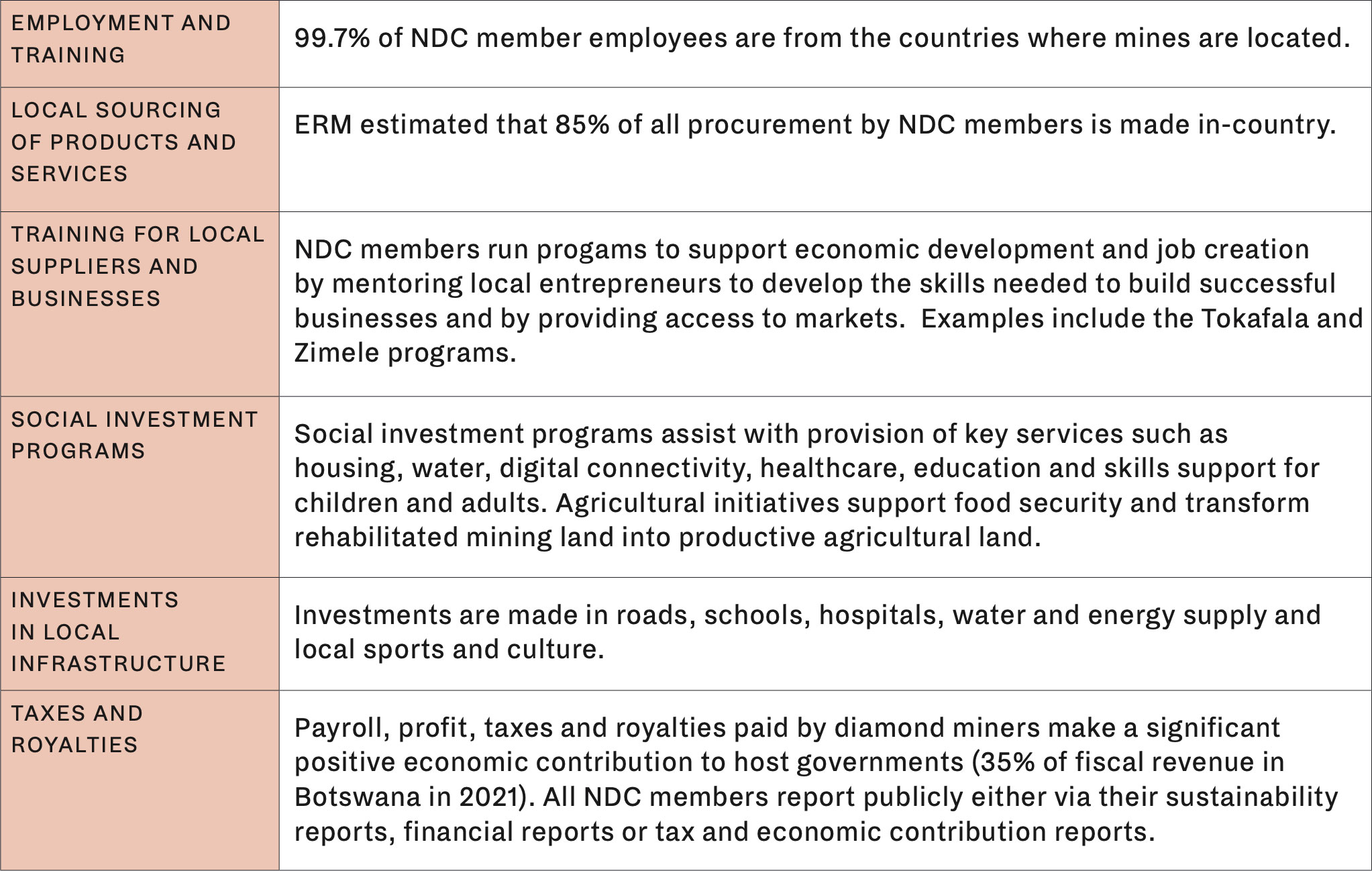

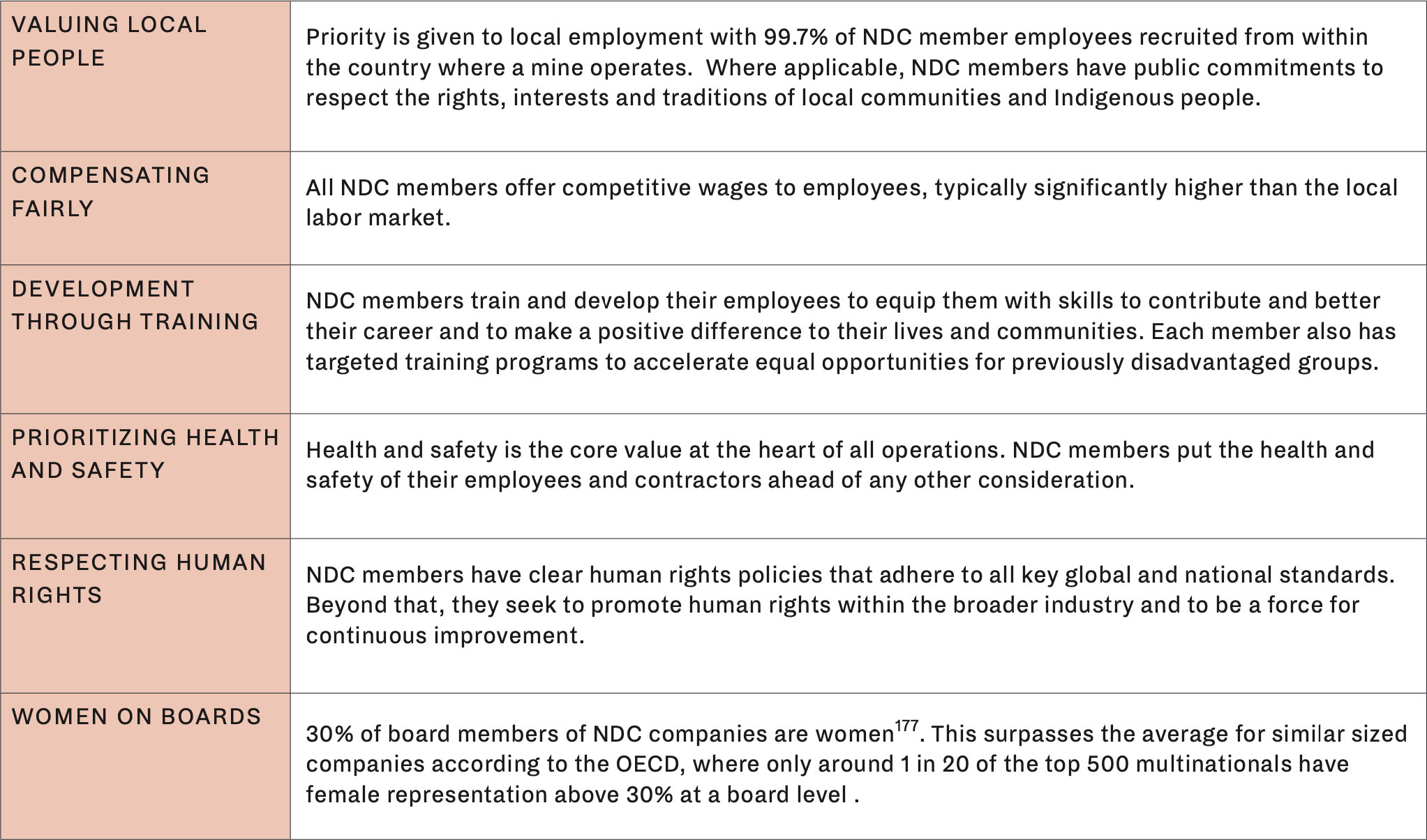

Table 3 – Summary of socio-economic benefits created by NDC members141

Research conducted by sustainability consultancy ERM determined based on 2019 and 2020 data that countries who host mining operations gain significant opportunities for development and industrialization, especially in regard to the purchasing of goods and services within a given region, which prevents a leak in investment and procurement being transferred elsewhere. It recorded that the total procurement spend by NDC member companies in these countries exceeded spend on wages, taxes, royalties and community investment combined142.

It was also reported that approximately $3.2 billion was spent with local suppliers, defined as those within the country of operation. This represented over 85% of all procurement spend143. These figures indicate how serious the natural diamond industry is about ensuring their operations benefit communities of host mining countries. In 2019, it was also recorded that the natural diamond industry has made a total economic contribution of at least $9.64 billion to local communities144.

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

Namibia neighbors Botswana and also demonstrates how positive socio-economic returns can arise from the natural diamond industry. Diamonds generate 20% of Namibia’s foreign export earnings and the country receives 80 cents of every Namibian dollar generated by Debmarine Namibia, its 50:50 joint venture with De Beers Group152. According to the World Bank, the adoption of new marine mining technologies for diamonds in Namibia in 2004 led to an increase in production and helped the economy achieve historically high growth of 12.3%. As of 2021, diamonds remain Namibia’s most important product in the mining sector, accounting for close to 68% of mineral output and 45% of foreign exchange earnings153.

It is not only regions in Africa that stand to benefit from the natural diamond mining industry. It is a foundational industry for the Northwest Territories (NWT) in Canada where it is the largest private sector industry and contributed 24% of total GDP in 2020154. Data from the 2021 Government of the Northwest Territories Socio-economic Agreement Report for Mines operating in the NWT recounts how the mining industry contributes to construction, transportation, retail and real estate, alongside the direct benefit of wages in 2021. Since 1996, NWT diamond mines have provided 32,137 person years of employment cumulatively and contributed over $24 billion to the economy. Of this, nearly $17 billion went toward NWT businesses and $7.5 billion to Indigenous-owned NWT businesses155.

SPOTLIGHT: BOTSWANA

The southern African nation of Botswana illustrates the power the natural diamond industry has to uplift communities and create a positive socio-economic impact. Diamonds represent 88% of Botswana’s total exports and the industry currently contributes around 35% of income to fiscal revenue145 and contributed 33% of Botswana’s GDP in 2021146.The development of the industry has helped Botswana avoid the resource curse and supported employment and growth in the economy through a focus on local procurement and development programs for SMEs such as the Tokafala and Zimele program, alongside investments in capital works and infrastructure147.

Revenue from diamond sales to the government is generated by income tax, royalties and a share of the company’s profits as dividends from Debswana, its 50/50 joint venture with De Beers Group148.

Debswana has existed for over 50 years and the venture held between the government and De Beers means that it sells 75% of its output to De Beers Group, while 25% goes to the state-owned Okavango Diamond Company149. De Beers is 15% owned by Botswana and the Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB) is 50% owned by the government of Botswana. The World Bank has reported that the arrangement that enables the government to generate revenue from diamond mining is approximately 80 cents of every dollar of profits generated by Debswana150. Activities like this have contributed to a rise in prosperity and per capita income, which following independence in 1967 stood at around $80 a year but in 2008 reached $6,000 a year151. Revenue from natural diamonds contributes to a school system providing free primary education to every child in Botswana.

The impact of contributions from Natural Diamond Council members

NDC members are dedicated to reinvesting and creating a positive multiplier effect across the communities they work with in line with their commitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, especially on areas surrounding alleviating poverty, decent work, health and wellbeing, fair wages and reduced inequalities.

According to an ERM report, NDC members paid close to $2 billion directly in salaries and benefits in 2019156.

Commitment to societal impact is underlined by the fact that NDC members invested over $165 million in social programs in 2019 that focused on community development initiatives related to agriculture, enterprise development, education and skills development, healthcare, and infrastructure158.

There are over 150 social and infrastructure investment and philanthropy initiatives that take place across various areas including agriculture, enterprise development, education and skills development as well as healthcare, sports, arts and culture. These activities generate $16 billion net profit annually .

Mining companies’ response during Covid-19 highlights their dedication to support communities. For example, during the pandemic, De Beers Group was active in Botswana and provided 24 clinics with Personal Protection Equipment (PPE), accommodation for medical personnel, food parcels for vulnerable households, water relief for local communities, 250,000 face masks from local SMEs, remote support for entrepreneurs, 20,000 liters of sanitizer produced in partnership, $50,000 to tackle gender-based violence and a PCR test machine for a hospital159.

SPOTLIGHT: DE BEERS GROUP HIV DISEASE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM

Natural diamond revenue is helping African nations work to combat HIV/AIDs. The De Beers Group HIV Disease Management Program was launched by Debswana in 2001 with the Government of Botswana. It was a first of its kind initiative aimed to tackle HIV and prevent, detect and treat HIV and AIDs and offers free antiretroviral treatment to employees and their families. De Beers Group recorded that 89% of employees knew their HIV status in 2018 compared with 26% in 2015, and that the uptake of HIV treatment has risen from 90% to 95%160. In 2020, they marked more than 11 years of no babies being born with HIV to De Beers Group employees or their spouses161.

SPOTLIGHT: DIAMONDS DO GOOD

Diamonds Do Good, formerly the Diamond Empowerment Fund, is a global non-profit that works to support initiatives that empower people and their development in diamond communities. It supports beneficiaries in Africa and India including the African Leadership Academy in South Africa, Botswana Top Achievers Program in Botswana, The Diamond Development Initiative in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Flaviana Matata Foundation in Tanzania and Veerayatan’s Colleges of Pharmacy, Engineering & Business Administration in India162. It aims to fund programs and provide grants that focus on high-quality education for younger generations163.

SPOTLIGHT: DEVELOPMENT DIAMOND INITIATIVES

Based in Nigeria, Diamond Development Initiatives (DDI) is a non-profit that works with an ecosystem of businesses, government and social services to encourage development and growth in businesses involved in diamond mining and promote sustainable environemtal and social impact.

In recent times, it has run projects such as operating mobile schools in countries like the DRC to help students pass exams. Through its programs over 200,000 miners have been registered in the DRC, 10 miners’ cooperatives have been formed and legalized, 121 children in mining communities have been given access to remedial education, 13 mining operations have been certified compliant to the Maendeleo Diamond Standards in Sierra Leone and several previously mined sites have been environmentally rehabilitated164.

The DDI’s work with Resolve

In 2020, the DDI joined forces with non- governmental organization RESOLVE to focus on responsible sourcing of artisanal diamonds by looking at conflict resolution, poverty reduction and heightened levels of social due diligence. They created the Maendeleo Diamond standards, which were the first set of standards for ethical artisanal diamond production and supply chain security165.

Their partnership work in Sierra Leone is focusing on land reclamation and restoration as well as reconciliation for communities affected by conflict. They are working to ensure responsible sourcing and help artisan diamond miners move away from poverty. The DDI has been supported by members of the NDC include De Beers Group and Rio Tinto, as well as retailers like Tiffany & Co

and Cartier166.

How are natural diamonds

ethically sourced?

FACTCHECK:

The industry is highly regulated. Under the Kimberley Process mandated by the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, all rough diamond trade is strictly regulated to ensure it is conflict-free. Multiple initiatives, processes and policies ensure that the industry moves beyond compliance on social issues across the supply chain. There is a robust set of checks and balances in place, including audits of the largest industry players, to enshrine the importance of ethical sourcing.

Ethical sourcing is essential to the practices of the natural diamond industry. It means that products and services across the supply chain are obtained in an ethical way. This includes upholding labor rights, decent working conditions, no child labor, the existence of health and safety measures and importantly, strong business ethics with respect for local communities166. In the context of diamond mining, this includes sourcing conflict-free diamonds.

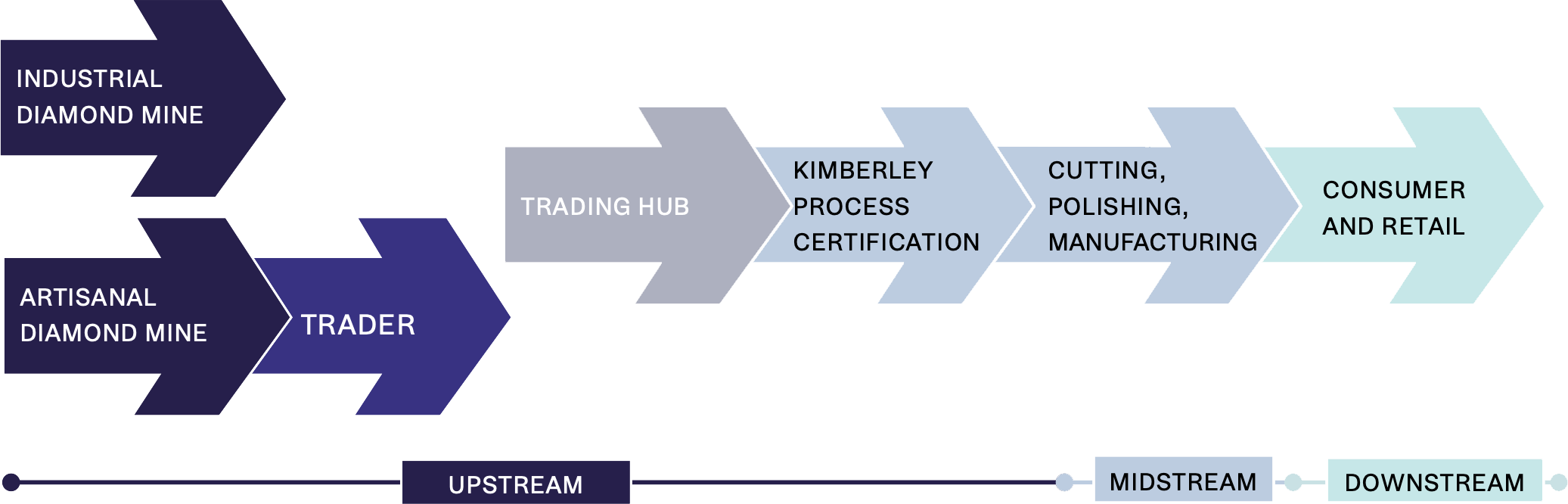

For many years, the natural diamond industry has worked hard to reform and address legacy issues related to mining practices and conflict diamonds. Now, the whole sector is held to extremely high trading standards. This is in part because 85% of the world’s diamonds by volume and 95% by value167 are extracted and marketed by large mining companies that are public entities which are held to account by shareholders and stakeholders for their social and environmental impact.

Pressure for mine-to-market supply chain transparency and traceability of diamonds has contributed to building the importance of ethical sourcing for the natural diamond community.