Solange Azagury-Partridge, The Thinking Woman’s Designer

“As I’ve gone through my career, my taste, my interests have evolved. I haven’t stuck with one thing. I keep exploring.”

If Solange Azagury-Partridge were a painting, she’d be a triptych. A book of short stories rather than a novel; a box of crayons instead of a pencil. After all, variety is the foundational touchstone of her jewellery vocabulary.

For the woman who’s keen on “subverting expectations,” the Solange universe is also one that defies pigeonholing.

This happy maverick draws inspiration from the constellations as well as from architectural constructions, lipstick, a touch of witchcraft (her childhood nickname was Witchy) and an unapologetic weakness for pattern and color. She’s also naturally hip; who else has a collection called “Poptails,” described as “a party on your hand,” or has “Nimrod Earrings” and a “Stoned Necklace,” an exquisite bib assemblage of cabochon and faceted gemstones?

Juxtapose that with her jewellery featured in the esteemed collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, and you’ve got a feel for the high-low world of Solange.

“I’ve always been very sure of what I like and my taste.”

Solange, who was born in London, was in her mid-20s and working three jobs when she became engaged in 1987. Already self-aware (“I’ve always been very sure of what I like and my taste”), the challenge was how to address the question that vexes every bride-to-be: but what about the ring? Indeed, for nothing seemed quite right.

“Estate jewellery felt quite adult, and I didn’t feel I deserved something so perfect, so pristine. I felt too young for an estate ring.” She also felt a bit squeamish about bridal as a concept. “I don’t really like the term ‘bridal.’ It means an engagement ring has to look a certain way, and channels people into a certain direction. An engagement ring should be beautiful and given in the correct spirit. It’s a symbolic gesture of love.”

Ring and Magic Ring from top to bottom

A ring of her own making was the only solution.

“The ring I designed, with an uncut diamond—it’s an octahedron—was quite possibly a lifestyle thing. I didn’t want to feel afraid or worry about its preciousness.” Not only did the ring enchant its owner, it created a following, and within a few years Solange had set up a studio, making jewellery. By 1995, Solange, the brand, was launched.

In 2001, designer Tom Ford made her creative director of Boucheron, a position she held for a few years before deciding to concentrate more fully on her own brand; in 2003, she was nominated Designer of the Year by London’s esteemed Design Museum. She’s even produced three short films. It’s all part of what sets Solange as a breed apart.

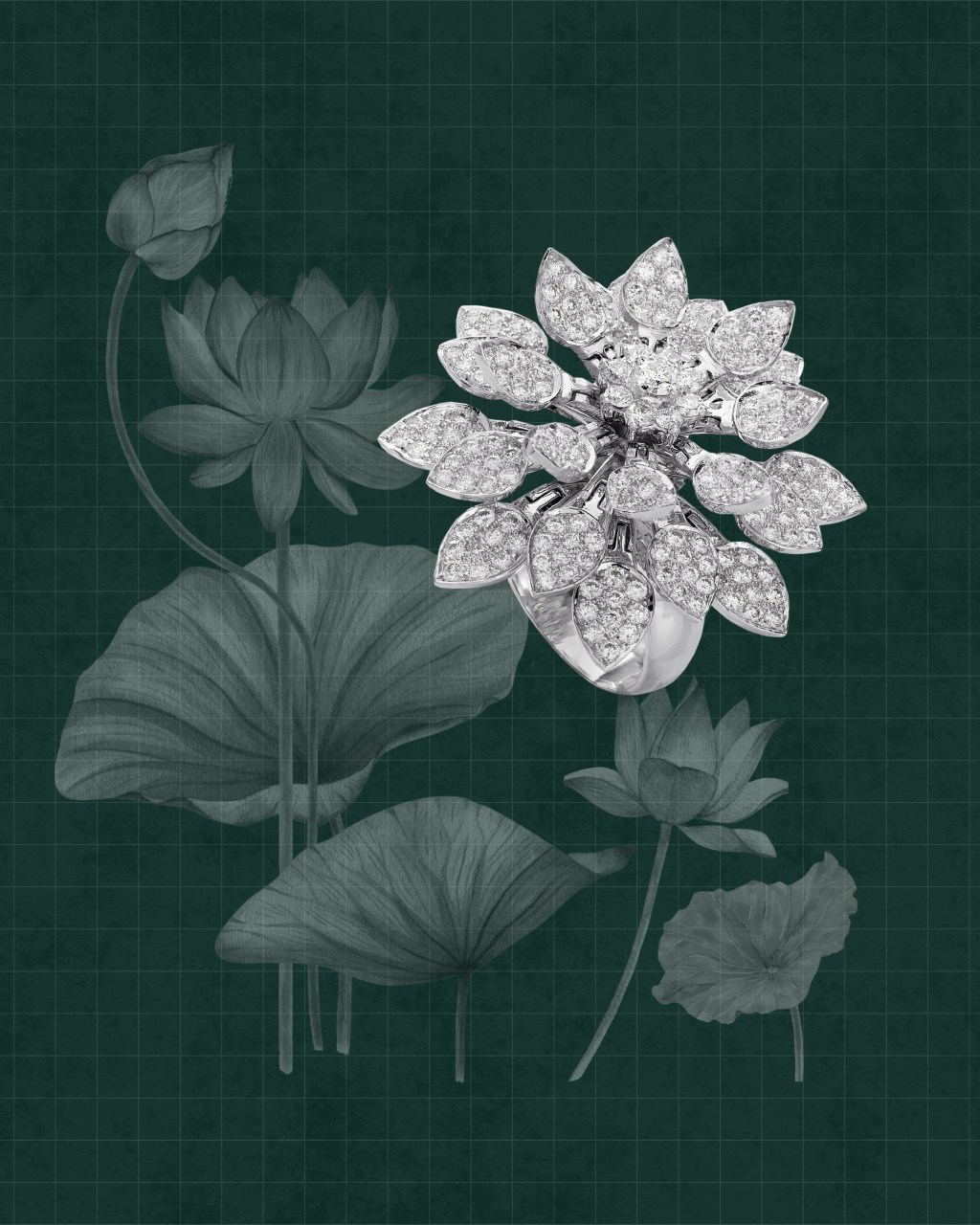

Today, Solange is the tour de force behind some 20 jewellery collections, each a reflection of her life, personal interests, and taste. Her first collection, “Platonic,” showcased “intergalactic diamond jewels.” For those challenged by higher math in school, Platonic is a cheat sheet of jewels engineered by wit, precision, and design, including the Ziggurat Bangle, made entirely of triangle-cut diamonds, or the Platonic Cuff, a sort of Star Trek matrix of a triangle, cube, and sphere with flashes of brilliant-cut diamonds. (The Platonic brochure cover looks like an M.C. Escher grid composed of triangle-cut diamonds.) While lines like Hot Lips have gained popularity and commercial success, others, including Alpha, Delicate, Tough Love, 24:7 and (my favorite) Everything, exist for their delightful provocativity and diversity. It’s this yin-yang—cerebral meets fun; sentiment meets sensation—that characterizes the through line in her many creations.

Diamonds range throughout the Solange collections, always in the service of shape and design—not size. To Solange, the triangle cut is “perfect,” whereas her love of the rose cut is about perception rather than perfection: “I prefer the spread rather than the depth of a diamond. The rose cut has more subtle light, it’s a bit more gentle.” She has a particular fondness for uncut diamonds, citing them for being “subtle and mysterious.” Take that one step further, and Solange concludes, “I do like when my diamonds don’t necessarily look like diamonds. An uncut diamond looks like a lump of nothing.” And yet, when it comes to actual design, inspiration begins with the stone, what Solange describes as starting “the old-fashioned way.”

Much as Solange is inspired by universal symbols, there are a few designers whose work resonates with her. To no surprise, each was an iconoclast, a trailblazer in his day: René Lalique for artistry, Andrew Grima for his “textured gold and his shapes” and David Webb for his “bold use of gold and opaque enamels.” But there is one other designer whose influence has perhaps deeper resonance: the great Suzanne Belperron. “She gives you the courage to follow your own beliefs. Can I do that? Of course you can!”

Solange may be a revered rebel, ever so slightly enigmatic, but in twenty-five years of being in business, she has never strayed from wanting to make her peers happy, and using jewellery to express love and tell stories. Her Notting Hill boutique in London looks like a three dimensional mood board or open diary, with its astonishing range of pretty much everything: found objects, bold color, leopard prints, psychedelic rugs, neon lights and a massive star-shaped chrome and glass table. The pièce de résistance is a riff on the chandelier earring—in this case, an actual chandelier made with 4 kilos of gold and 200 carats of white diamonds. The result, like Solange, is pure seduction and brilliance.