The Dazzling History of Diamonds and Weapons

As symbols of power and indestructibility, iconic diamonds have a synergy with the weapons. Embedded in swords, daggers, guns, and even used as poison rings, natural diamonds have long added a mystique and luxury to the weapons of the elite. So, what are some famous (and notorious) stories of diamond-studded weapons from the near and ancient past? How did these weapons convey sovereignty and inspire awe? And did rulers really carry their epic diamond weapons into battle?

Image: Squadron14; sword and dagger photographs: Public Domain

Historical Legacy: Diamonds as Symbols of Power and Prestige

India was famous as the only known source of natural diamonds until the nineteenth century, so rare diamonds became part of the epic stories of Sanskrit literature going right back to the Rigveda. In Hindu mythology, the god Indra wields the legendary vajra, one of the most powerful weapons in the universe, a club-like weapon that combines the indestructibility of a huge diamond with the irresistible force of a thunderbolt. Forward wind to the present era, and imaginary diamond weapons continue to hold their allure, with James Bond saving the world from an all-powerful diamond laser orbiting in space in the 1971 film ‘Diamonds are Forever’.

History, however, tells a rather different story. Weapons with diamonds were rarely objects of violence used in actual situations of combat. They were ceremonial arms of incredible craftsmanship that spoke of power, prestige and rulership. Here are four examples, covering four centuries from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries.

Mughal Court’s Gem-Studded

Daggers and Swords

Descended from the famous empire builders, Timur and Genghis Khan, the Mughals retained many of the itinerant traditions of their Turko-Mongol ancestors. In the gift-giving culture of their court they laid tremendous importance on the luxury objects that were worn on the body, traditionally used in hunting and warfare – clothing, jewellery and arms and armour. As the stability and wealth of the empire peaked in the first half of the seventeenth century, the hilts of knives, daggers and swords worn at court ceremonies became increasingly gem-studded. A personal dagger of Shah Jahan, c. 1615, is one of the most sumptuous examples, with a hilt of pure gold, set with over two thousand natural diamonds, rubies and emeralds. The very top of the dagger has the largest dazzling diamond cut to a point to complete the finial. Given to him by his father to celebrate his military successes, it draws on central Indian forms of design and thus was a carefully crafted political statement about the dominion of Mughal rule.

The Ottoman Sultan’s Jewelled Gun

Just over a hundred years later the jewelled gun of the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud I (1696-1754) has secret compartments for a dagger and pen case. The opening is behind the exquisite diamond encrusted insignia of the Sultan, and thus expresses an idea of kingship that valued marksmanship and calligraphy, two skills required of rulers. The jewelling is attributed to an Armenian Christian, Hovhannes Agha Duzian (d. 1744), who was chief goldsmith. The gun was never shot, so it clearly functioned as an important piece of regalia, fitting for the Ottomans as the leading experts in firearms from the late 15th century.

The Ceremonial Diamond Sword of Napoleon Bonaparte

One of the first swords to have very large natural diamonds is the ceremonial sword of Napoleon Bonaparte, with 42 brilliant cut diamonds as a total weight of 254 carats, including the famous Regent diamond. Named after Philipe II, Duc de Orléans, Regent of France for Louis XV, who acquired it in 1717, the notorious ‘Regent’ diamond had a turbulent history. Discovered in the late 1680s/90s at Kollur mine in Golconda, the enslaved worker who smuggled it out (reportedly in a leg wound) was soon murdered by a British sea captain. By the late eighteenth century, the epic diamond was symbolic of the lavish culture of the Court of Versailles. It was stolen at the French Revolution in 1792 along with the French Crown Jewels. By 1797 it was used as security to finance the Italian campaign through which Napoleon rose to power, meaning he viewed it almost as a lucky charm. His decree was thus issued on 10 October 1801, “The Minister of the Interior will have a sword made for the First Consul of the Republic on the hilt of which will be placed the diamond known as ‘The Regent’ with the assortment of diamonds that are deemed necessary.”

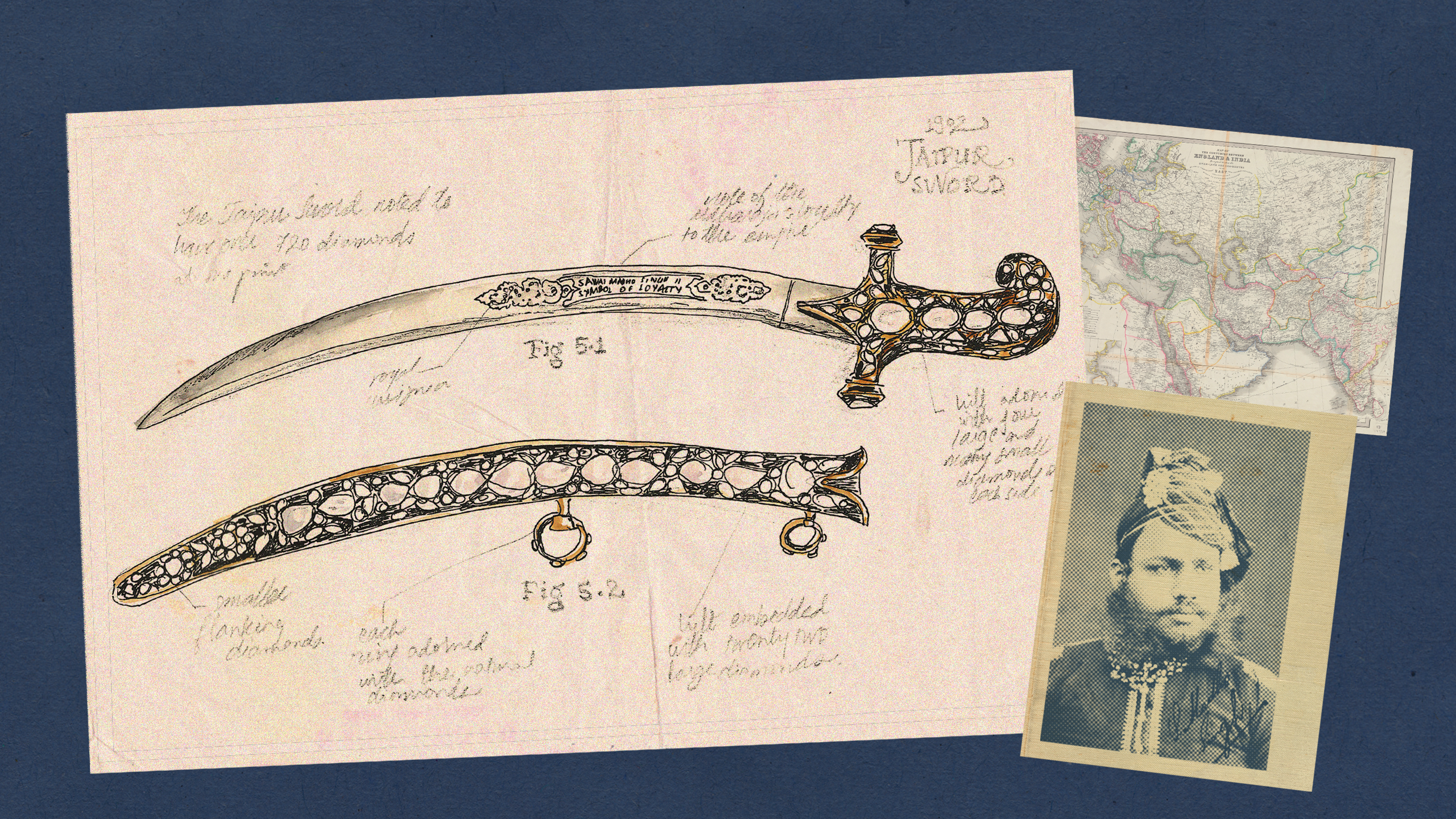

Symbolism and Craftsmanship of the Jaipur Sword

By far the most lavish natural diamond sword and scabbard has over 2000 carats, almost ten times Napoleon’s sword. Known as the ‘Jaipur Sword’, it is so opulent it is almost like a lightsaber. The sword was commissioned by Sawai Sir Madho Singh II, Maharaja of Jaipur as a gift for the British King Edward VII, eldest son of Queen Victoria, to mark his coronation in 1902. The sword was made in Jaipur by the Jain goldsmith, Seth Banjilal Tholia, some with 18th-century rose cuts,and others with brilliant cuts, reflecting faceting techniques not earlier than the 1890s. They are arranged in a pattern of lotus flowers with gold and enamelling.

“As a piece of craftsmanship, it showcases Jaipur, encapsulating the city as a centre of gemstone trade and enamelling. It is a perfect example of gift-giving that is both imperial and local, bringing a vision of India, and more specifically Jaipur, to the world.”

Edward VII’s connection to Jaipur went back to his 1875 visit when the town was (re)painted pink for his arrival as Prince of Wales. In 1902, Maharaja Madho Singh was invited to his coronation as king in Westminster Abbey. As the Maharaja did not trust the English water, he famously had two huge silver urns made that could hold 9000 litres of Ganges water, to use on his three-month journey to England. They stand proudly in the Jaipur City Palace to this day.

The steel blade of the Jaipur sword had an inscription in English professing loyalty to the British King. But does the gift say more than this? It speaks of the extraordinary wealth of the Jaipur Maharaja and presents him as an equal to the English crown. As a piece of craftsmanship, it showcases Jaipur, encapsulating the city as a centre of gemstone trade and enamelling. It is a perfect example of gift-giving that is both imperial and local, bringing a vision of India, and more specifically Jaipur, to the world.

Important Diamond weapons were far too valuable to risk losing on the battlefield. These were not weapons for violence, but weapons invested with enduring notions of sovereignty, wealth and political power.