Celebrating 20 Years of the De Beers Diamond Route

In an otherwise typical Tuesday, I time traveled to the future.

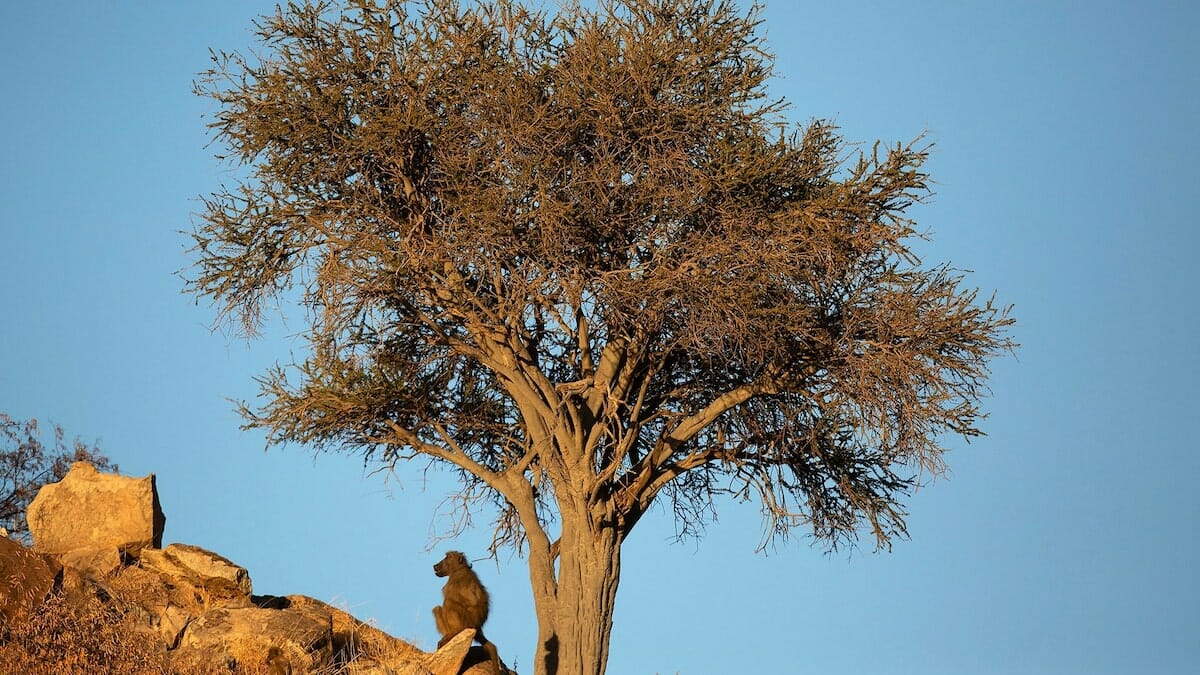

The destination was Southern Africa, home of the famed Diamond Route that counts approximately half a million acres of conservation land across seven nature reserves. For a science geek and New Yorker like me, these hubs of biodiversity—and zebras!—are dream destinations, AP Bio refreshers, and also six hours ahead of my time zone. But besides being literally advanced, the Diamond Route is forward-thinking, too, especially when it comes to ecological protections.

“One of our main focuses right now is rewilding,” explains Eben Van Heerden, the Ecology Manager of De Beers Group who is responsible for the Reserves in South Africa. “Rewilding is where certain species occurred and doesn’t occur anymore or have very low numbers. We have re-introduced 39 buffalo this year into the Venetia Limpopo Nature Reserve as buffalo naturally occurred in this part of South Africa. The buffalo came from Dronfield Nature Reserve where De Beers had been breeding TB free buffalo since 1990.To reintroduce them where they naturally occurred, that’s part of our conservation. We want to establish big herds again… we’ve got lions, elephants, giraffe, sable, roan and various other plains game as part of the rewilding process, too.”

Read More: Buying Sustainable Natural Diamonds Leaves A Positive Impact

That process is the latest in the Diamond Route’s evolution, which began 20 years ago and now fosters and protects diverse habitats like savanna grasslands, arid plains, and riverine woodlands. “The nature of mining for diamonds is that you have these incredibly secure areas,” explains Erin Parham, De Beers’ Head of Biodiversity. “The mine site itself is often surrounded by quite a large area that acts as a buffer zone. 20 years ago, De Beers and partners asked, ‘What if we used that land to protect biodiversity and increase protection for wildlife?’ It presented a really unique opportunity to restore and regenerate those areas, with protection from human development and other threats.’

Read More: De Beers Announces First-Ever Celebrity Global Ambassador

That means endangered animals like elephants, lions and leopards get their habitats protected, while native plants have a chance to rebuild their root networks. “Nature is highly adaptable,” Parham notes, “But when [humans] push it over the edge with habitat loss and poaching, coupled with changing climate conditions, it really starts to transform how species can or can’t exist in their own ecosystems. Our goal is to restore and regenerate those ecosystems to their natural state, and provide secure protection into the future, so we leave the land and its wildlife better than we found it.”

“It’s important that we can show what we’re doing in terms of conservation,” Van Heerden adds, “Because we’re a mining company and there are certain assumptions about how those types of businesses treat the land—and we’re doing the opposite! But also, I like to show what we’re doing in terms of conservation because we’re doing so much! And it’s working!” He boasts. “We’ve really upped our responsibility to the environment since the Diamond Route was founded and made an impact in the whole of Southern Africa with our rewilding programs. It’s not just about natural diamonds. It’s about doing the right thing for the natural world.”

Eben jokes that when he clocks into work every morning, “my office is 100,000 hectares big!” But lately he’s been working to support African buffalo herds by moving them from their adapted habitats to their natural grazing grounds. “Because of farming, we really lost a lot of them, but in the past few decades, we’ve really been working to rebuild their natural habitat, and then relocate them so they can live the way they’re meant to. There used to be thousands. We have about 350 buffalo on the Dronfield Nature Reserve, situated near Kimberley now, and can I say they’re my favorite animal? They really are!” Van Heerden admires the animal’s “majestic” size, which can grow to 1200 pounds, but also their firm family structures, which echo many human relationships. “The bull is dominant scientifically,” Van Heerden says, “But I’ve been around them enough to know that most of the time, the ladies are really the ones running the show.” Van Heerden notes that zebras also develop tight family bonds. “If you break them up, it can take them two years to accept anyone else as part of their group,” he says. “They miss their family, just like humans do! So we need to be very careful when we relocate them to more fertile grazing ground, because they need to be kept together no matter what.”

Parham’s favorite animal is the brown hyena. “Hyena have a menacing reputation, but for brown hyena it couldn’t be further from the truth” she laughs. “They have a very safe place in our reserves. Because they’re scavengers, they are such an important part of the Diamond Route’s ecosystem. They clean the landscape of decay and put everything back into its proper place… Being largely nocturnal they’re [also] quite elusive and a little bit cryptic, which I like a lot.”

If you want to see the efforts on the Diamond Route up close, you are in luck. Some locales, like the Camelthorn forests of Dronfield, readily welcome visitors with onsite accommodations. Others, like the grassy plains of Benfontein, support research programs for scientists and students to gather firsthand data of rewilding efforts.

Saving your money for one of Karen Elson’s diamond accessories instead? Zoom yourself into the future for free by clicking on the Diamond Route’s live cam, where you can watch elephants, buffalo and zebra thriving in their natural habitat—just six hours ahead of NYC, but moving into a better future thanks to 20 years of conservation efforts, and counting.