Earth Day: This Scientist is Sharing the Truth About Sustainable Diamonds

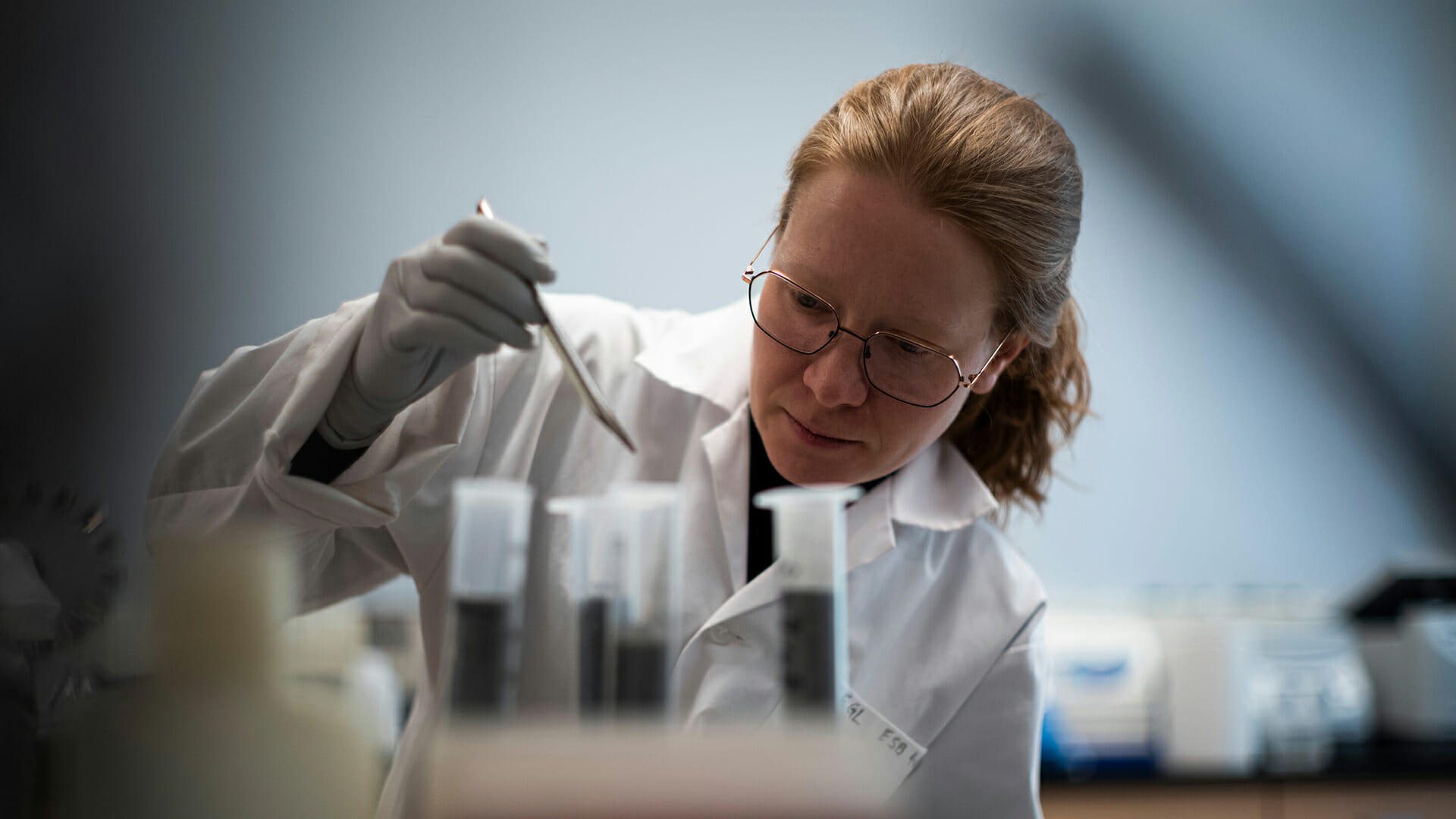

In her 30 year career, environmental scientist Allison Rippin Armstrong has dug up some truths about natural habitats and natural diamonds.

You can’t talk about Earth Day without mentioning sustainable natural diamonds—after all, each one has been on the planet for at least one billion years (really!) and comes directly from the earth’s dynamic core. Bringing those gems to the surface takes skill and care, especially if you ensure the wildlife and communities surrounding them are treated as their own precious entities. (Spoiler alert: we do.)

Enter Allison Rippin Armstrong, a scientist on the forefront of environmental protection and sustainable mining. It’s her job to make sure when it comes to natural diamonds, people and the planet get an equal seat at the table—and she’s been coming through on that promise for over 30 years.

Read More: Meet the Rebel Women of the Diamond World

Here’s how the Nova Scotia resident began her career, how Indigenous communities inform her work, what it’s like being inside a mine, and how diamond lovers might soon be wearing a literal carbon footprint on their fingers.

When you’re at a cocktail party and someone says, “What do you do?” how do you answer?

I tell people that I’m a practitioner, and somebody who’s passionate about environmental and social excellence and governance. I’m also an advisor, but you know, I’d never consider myself an expert.

But you are an expert!

But I’m always amazed when people label themselves as experts! How can you have nothing left to learn?! I’ve been doing this for 30 years but I’m still continuing to learn. It’s an ever-changing space, and how could you be an expert in something that is changing at a lightspeed pace? So I say I’m more of an advisor, a practitioner, and a learner. That’s how I describe myself.

What made you want to get involved in the diamond world?

I considered myself a bit of an activist, and I’d heard so much about mines from an environmental perspective that I knew I had to see one. So I went to a gold mine in Northern Ontario, Canada, and I was fascinated. I was 21 and I had so many questions!

What is a mine actually like?

It’s so much more than a site in the ground. It’s really a community and a small business unto itself. Whenever I go to a mine, I speak to employees. I speak to some of the local businesses in the town. I speak to residents, because residents are the experts of their own home, as well as environmental scientists. And from that very first mine, I was so curious about the whole industry and its impacts, so I started asking questions, and I realized I was very passionate about doing this the right way, and learning from the people on the ground.

What was your first job?

I worked with Indigenous organizations and governments, especially the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, and then the Dene Nation that worked on behalf of all the Dene living in the Northwest Territories, and some other provinces as well—because after all, a Canadian province is a colonial delineation, and not a reflection of indigenous traditional territories. And although I had a formal education at a university, this was my real education. I am so fortunate to have spent time on the land with [Indigenous] Elders because, you know, that’s what put everything that I had studied at my university into a practical context.

What’s something you learned from those Elders about environmentalism?

When scientists talk about land—when I had been talking about land as a biologist—you think of how there’s land, there’s air, there’s water… we break things up into different categories, and different habitats. And when I was with the Indigenous Elders, and they talk about land? It’s everything, because it’s all connected. Also, they’re not just talking about what you can see and feel and experience right now on the land. They’re talking about historically, currently, and in the future. Another time, I was standing on the side of the Yukon River. I was talking to some elders from the First Nations in the area, and they’re talking about songs and stories that their grandmothers had told them, that their grandmothers’ grandmothers had told them! And I realized that the people that I was standing with, were connected to this exact spot in a way that I will never be able to comprehend.

How does that view of the planet and its wildlife contribute to your work with diamonds?

We look at what the baseline pre-existing conditions at a mining site already are, what the impact is during operation, and how it will impact the world in the future. In their eyes, the time we spend on earth is just the blink of an eye, right? We need to look at these things from a fulltime spectrum. The diamond has been on earth longer than we have, and it will be on earth longer than we will be. How do we ensure that those who come after us still have a world for that diamond?

In your view, how can environmental justice and diamonds co-exist?

That’s such a great question. You know, for people who work with diamonds, they’re not luxury items. They’re jobs. They’re money put back into the community. They’re money put back into the protection of the land. And they’re doing it specifically—at least in my work!—with input and benefits and leadership from the Indigenous communities who are the original stewards of the land. And where I’ve worked in Botswana and in Canada, I’ve seen diamonds turn not just into jobs, but schools and farms. In Botswana for instance, the mining companies know they need to invest in food production and food security in order to work with the land and its people. They’re investing in teachers for their schools, and in sustainable agricultural techniques and experts to help with farming practices. Diamonds mean roads, hospitals, nursing stations, clean water facilities, and things that mines fund and bring into areas. And they bring female empowerment.

Ooh, how are diamonds part of a female-led economy?

In Botswana, I actually had a woman say to me, “I am the product of diamond mining.” And what she meant was, her education and her university (all in country) were funded by the mines and their foundations… It’s also important to note that if you go to a diamond mine, and you look around, you’ll see women at the top of so many parts of the industry. There are women driving the equipment, women who are geologists, women who are electrical and structural engineers. And funding women funds whole communities—children, elders, everyone. It’s the best investment you can make.

Is it true that some natural diamonds can capture carbon from the atmosphere?

Yes! It’s been proven that certain kimberlites can sequester carbon from the air. There’s a lot of money going into that research right now. There’s also great progress happening on the environmental front.

How else are researchers making environmental progress through diamonds?

I am very happy to see globally, that there are a number of companies that have made commitments in terms of climate action… I wish we could see more of that in other industries, and in other spaces as well! I’m really happy to see that increasing and sustaining biodiversity at [mining] sites is becoming the rule… The way water is being conserved and protected is important, too. And I’m really excited to see the number of companies that are moving toward renewable energy and incorporating renewable energy into extraction techniques. We’ve got solar panels being installed as a main source of power, so not only are you seeing mines minimize their impact, you’re also seeing them invest in technology and resources that actively put resources back into the planet.